A UN expert walks into a bar…

Extract from our new publication ‘Silence’.

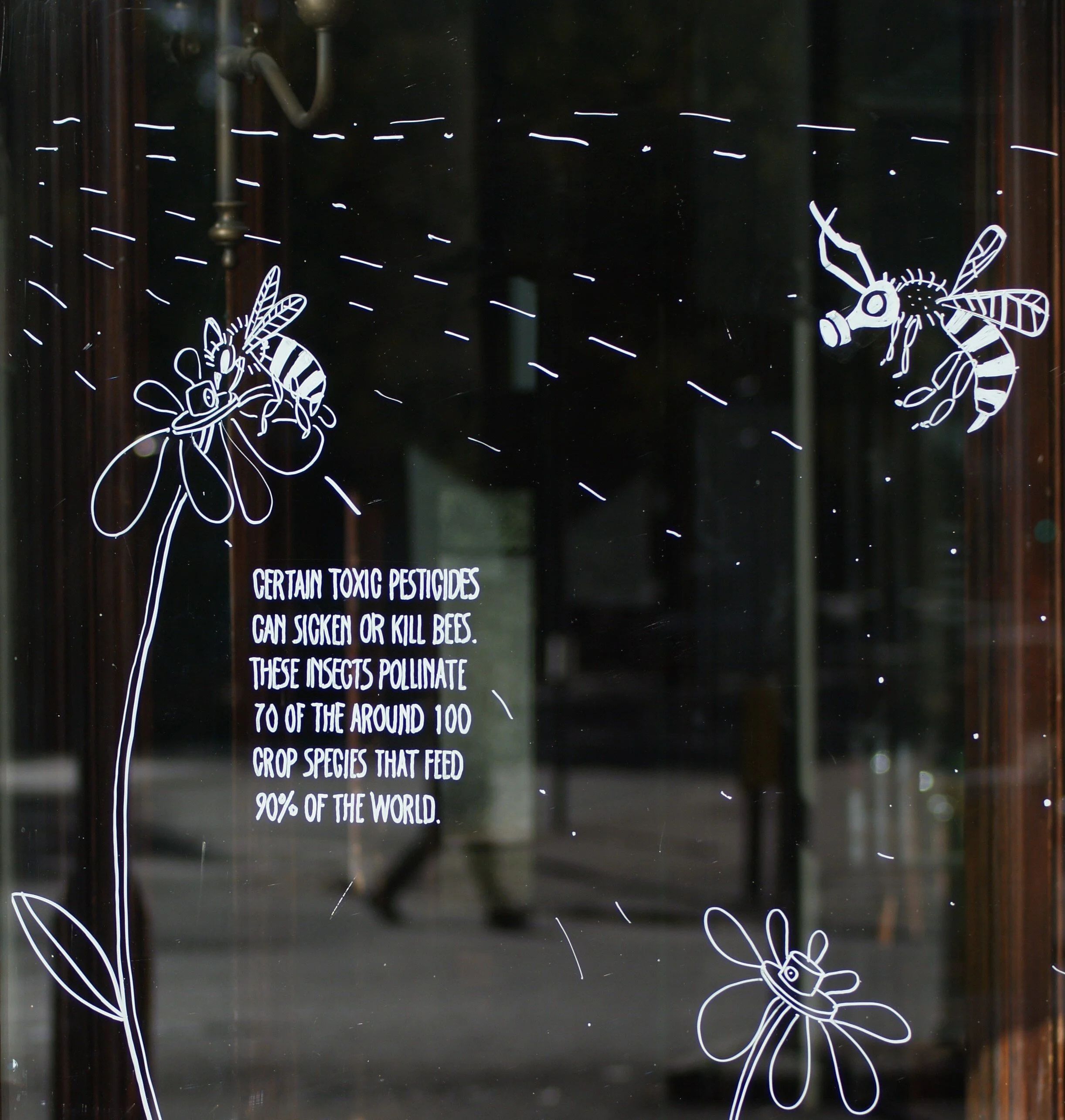

A window illustration at The Three Stags pub in London, drawing attention to the damage certain toxic pesticides can do to bee populations.

In 2014 Baskut Tuncak was appointed as the UN’s top expert on human rights and toxics, a topic which some of the world’s governments have argued is not a human rights issue at all.

Since then he has seen the best and the worst the world has to offer when it comes to hazardous chemicals, ranging from visionary regional legislation and access to information to outright denial of responsibility and repression of environmental defenders.

The last time he was in London on official business in January 2017, he wrote that it was plagued by air pollution, noting that toxic elements in the air contributed to as many as 40,000 premature deaths each year. Tuncak also spoke about the damage Brexit could do to, including allowing environmental regulation to stagnate or backslide, guaranteeing citizens fewer legal protections.

So why did he come back?

Two windows at The Three Stags pub, Lambeth.

Last Sunday he visited The Three Stags pub in London as part of a public conversation and art exhibition on the toll everyday exposure to toxics could have on human health and ways for individuals to make a difference.

In conversation with Veronica Yates, Director of Child Rights International Network, Baskut described the challenges posed by the increasingly everyday nature of toxic exposure and the level of pollution skyrocketing virtually everywhere.

Surrounded by artwork by Miriam Sugranyes, the UN expert discussed problems (like a culture of silence, a lack of information and the huge power of those who create toxic waste) while emphasising that there are solutions.

Companies are being forced to change, governments are making improvements even as they reject his recommendations, and individuals have gained compensation for themselves and others after years of campaigning.

Speaking about the case of one South Korean activist who inspires him, Tuncak recalled how some activists have risked their lives and dedicated themselves wholly to the cause despite the odds.

“For many years he was offered compensation by Samsung, repeatedly, essentially hush money, but he never took it. He certainly could have used the money but he never took it and he, around him, developed this whole campaign and movement to get Samsung electronics to phase out certain toxic chemicals. And to get them to acknowledge their responsibility and liability, not just for his daughter’s death but over two hundred alleged deaths at this point.

“Stories like that give me hope,” he explained, adding that “there are people that recognise the impacts and are willing to campaign on this issue, and to take a stand for more progress across a whole number of industries and across a number of countries.”

Despite the “unholy alliances” between fossil fuel producers and the petrochemical plastics industry, Baskut explained how European campaigners have produced an app which sends legal requests for information to companies at the push of a button.

Once such a request is received, the companies are obliged to respond, detailing any toxic chemicals contained in the products they make. The app, previously only available in Germany, is now being upgraded to work throughout the European Union.

“Just the fact of having to generate health and safety information about chemicals is enough to drive companies away from using that substance,” explained Tuncak. “They know what the risks are”.

Bringing complaints before the UN is also an under-used strategy according to its resident toxics expert.

“Countries don’t like to have issues brought to the Human Rights Council regarding themselves and I don’t think the issues of pollution are being brought enough.

“In many cases it gets more consideration than saying: this is the right thing to do.”

Despite the many state and industrial powers arrayed against him, Baskut remains uncharacteristically cheerful in a line of work which has been known to hand out nicknames like “Dr. Doom”.

“I feel a lot of optimism,” he explained at The Three Stags, “because I know there are a lot of good chemists out there and a lot smart, talented people, and I personally feel like there is huge untapped potential to transition towards safer chemicals, safer products, safer ways of doing things.”

Couldn’t make it? Not to worry — you can access an online version of the gallery of children’s rights and toxics, and learn about what you can do to reduce your exposure to toxic chemicals.