The Power of Language

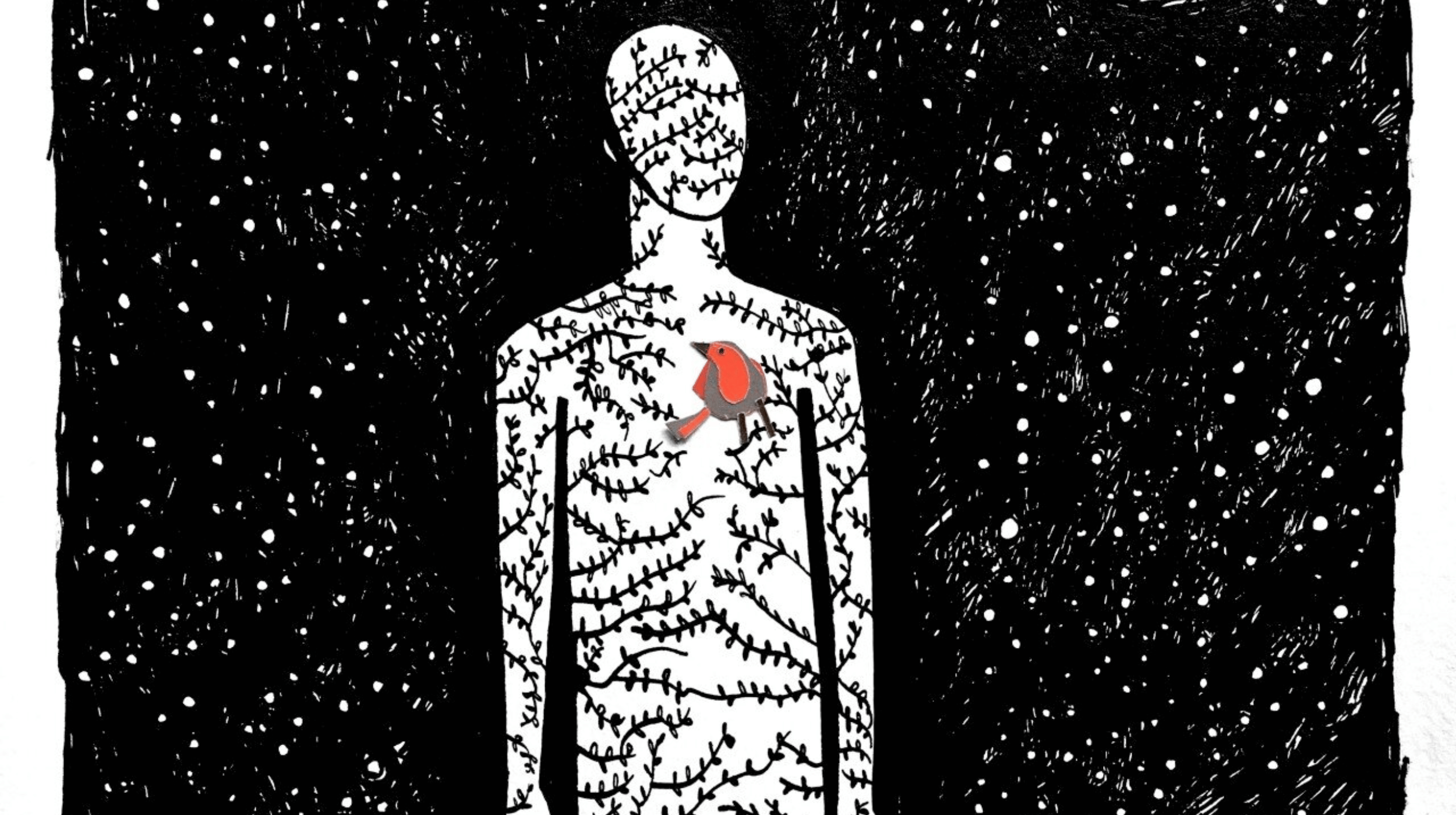

Language isn’t just about words, even if dictionaries state otherwise. Most of us communicate through words, yes, be they written, spoken or signed, but most communication comprises facial expressions, physical cues and ‘speaking’ with our eyes, aka body language. Irrespective of its form, however, language serves the social practice of understanding one another, which, as a species, is important to us, but it’s not the only reason why we do it. Essentially, language is used to communicate ideas, and because of this, it harbours a power we’re rarely conscious of.

Let’s take an obvious example: dictatorships. Power-hungry tyrants and their cronies use language — from words in televised speeches to images in propaganda — to spread an idea to garner uncritical support and gain adoration and fear from the masses. Meanwhile dissenters use language — from words in speeches at secret gatherings to images in anti-government posters and pamphlets — to destabilise that power by encouraging criticism and inspiring rebellion.

This ability to convey an idea and instil it in an audience’s mind shows the power that language can have as a means of communication. A given idea can then either spread or die, change opinions or reinforce them, keep people in their place or rouse them, or it can evolve into more ideas each with their own or it can stagnate and paralyse thought. But at its core, the power of language is something bigger. While it may appear simplistic to say that if we can use language to convey an idea, we can do the same with a counter idea, it’s precisely here where its true, elemental power lies, as no single idea, however dominant it may be, exists without opposition, criticism or questioning, and this is always done through language, whether it’s voiced, drawn, gesticulated or otherwise communicated. In other words, language has the power to subvert power, both its own creations.

“We live in capitalism. Its power seems inescapable. So did the divine right of kings. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings. Resistance and change often begin in art, and very often in our art, the art of words.”

— Ursula Le Guin

Random reflections on the power of language

Democracy

No single person or institution can monopolise language, however ‘powerful’ they may be, as language is, by its nature, democratic. Simply having a command of a language — written, spoken, signed, drawn etc — means that we can use it however we like and to communicate whatever we want.

Humility

On resisting tyranny, one author advises: “Avoid pronouncing the phrases everyone else does. Think up your own way of speaking”. This relates not only to chanting the same words (and ideas) as others do or expect from us, but also resisting a narrowing of our vocabulary and thoughts. The world is full of information from myriad sources, and this diversity calls for us to be humble and recognise that there’s so much more we don’t know, and to allow ourselves to challenge our own thinking and be open to being proven wrong.

Challenge

‘No’ is a powerful word because it stops people and their assumptions and expectations in their tracks. A firm ‘no’ from an adult to a child can prompt obedience, but this effect is as much about the meaning of the word as it is about solidifying one’s authority in a power dynamic that places the older and bigger person in charge and the younger and smaller one in compliance. But ‘no’ works both ways, and while such an exclamation can be obeyed, it can also be challenged, as ‘no, you can’t’ leads to ‘no, I can’.

Fear

Institutions and individuals use language both to build their power and to maintain it. In human trafficking, victims are often groomed not through physical submission, but through language that disempowers, dehumanises, degrades, isolates and shames them into compliance. Meanwhile in the case of politics we have demagogic rhetoric, whereby the objective of a simple sentence (and the idea it carries) is nothing more than to convince voters by stirring their fears and desires.

Protest

That actions speak louder than words is difficult to refute. When Rosa Parks refused to stand up, that action spoke to many people without a single word. After the Tank Man stood in front of a convoy in Tiananmen Square,it eventually became one of the most iconic symbols of protest. And such actions are sometimes captured on camera, reminding us, too, that ‘a picture is worth a thousand words’.

Dominance

Asserting power and dominance requires obedience from others, but obedience isn’t just achieved through coercive means such as force and violence; the mere threat of these is enough to induce it, and this is done indirectly through language. When something is ‘banned’ and ‘will not be tolerated’ is sometimes enough. A clenched fist or a stern look can also suffice. Language, however we express it, can be loaded with assumptions of power and authority which, whether real or perceived, makes us react and act a certain way.

Identity

Commanding a language and being understood forges a powerful feeling of belonging — to a family, a community, a culture or a country. This is especially true when discussing national identity, but not all citizens can talk of having a national language. Outside of Europe, for instance, Dutch, English, French, Portuguese and Spanish are inescapably the languages of the colonisers, as language is never ahistorical or apolitical, especially when you know one stripped you of your own.

Assumptions

When we communicate through words, it’s the result of using grammar and vocabulary to translate our thoughts and feelings, but words also affect the way we think. The media, for instance, uses particular words, images or other techniques to affect the way audiences perceive something. Calling young people ‘snowflakes’ or refugees ‘marauding migrants’ can sway public opinion on these groups, as labels are always charged with assumptions and expectations.

Compliance

The language of telling a child to sit like a girl or that they’re such a brave little boy doesn’t stop at the last word; it continues in the actions that follow. Legs together, feeling of shame for crying… these are the unspoken expressions of compliance, when we do as we’re told and grow into a broad brushstroke of an idea that we had no say in designing.

Stereotype

Labels and stereotypes mislead us into thinking something or someone is only a particular way. Such assumptions abound especially for groups who’ve historically been downtrodden: women, children, people of colour, immigrants, religious groups, sexual minorities, and so on. For girls and women, labels can range from ‘Angry Black Woman’ and ‘Dutiful Wife’ to ‘Feminist Killjoy’ and ‘Pretty Princess’. And when we replicate these labels uncritically, we feed the stereotype.

Diversity

Generic terms are convenient terms, but they limit our perception of things. ‘Man’ or ‘mankind’, for instance, are supposed to be all-encompassing, but they’re far from inclusive of the diversity of humanity. Similarly, ‘child’ is taken to include girls, boys, infants, adolescents, teenagers, and youth, yet rarely is intended to mean all of them at the same time.

Freedom

All the words we’re not supposed to say, let alone come to know them. Some words are ‘dirty’ and can get us into trouble, but not in the way we’re probably thinking. Depending on the country, talk of freedoms and rights gets people in detention and forced labour camps or shot and buried, because such words need to be silenced, it’s believed, because they are a risk to the status quo. But it’s not because the words in and of themselves are dangerous; it’s the ideas they carry.

BUT…

Language on its own has little purpose if no one is paying attention to what we express. We may hear, see, feel or otherwise perceive someone communicating with us, but it’s not the same as taking in the content, understanding the meaning and acting on it. Part of the issue is that ‘listening’ is a disappearing art, as nowadays we place too much emphasis on ‘talking’ ourselves, and some groups, such as under-18s, are more prone to this treatment than others. Needless to say that the ‘future leaders of tomorrow’ are apparently not worth hearing out until the future arrives. And when we speak for them, whether it’s well-intentioned or self-righteous, it doesn’t necessarily make their message louder; it merely reinforces our role as self-appointed mouthpieces.

This content originally featured in the magazine Power, which is free to download here: http://bit.ly/CRIN-Power