After three decades of climate talks, can COP30 bring the change we need?

Before COP30 in November, CRIN is critically reviewing the Just Transition Work Programme (JTWP) and the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) of States: two initiatives aimed at enhancing the implementation of the Paris Agreement and the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). How can UN climate talks ensure both children’s rights and human rights are centred when discussing societal, sectoral and economic change?

The 62nd sessions of the Subsidiary Bodies (SB62) in Bonn wrapped in June, marking the official starting line for what could be one of the most pivotal climate COPs. During SB62 States established a critical agenda for COP30, with key deliverables including establishing a just transition framework, defining a global goal on adaptation, updating the gender action plan, scaling up climate finance and delivering the NDCs before the end of 2025. With these goals in mind, this year’s COP has the potential to deliver on real climate action.

Amidst these high-stakes negotiations and deliverables post-SB62 and pre-COP30, CRIN is following two key areas: the Just Transition Work Programme (JTWP) and the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) of the States.

Just Transition Work Programme

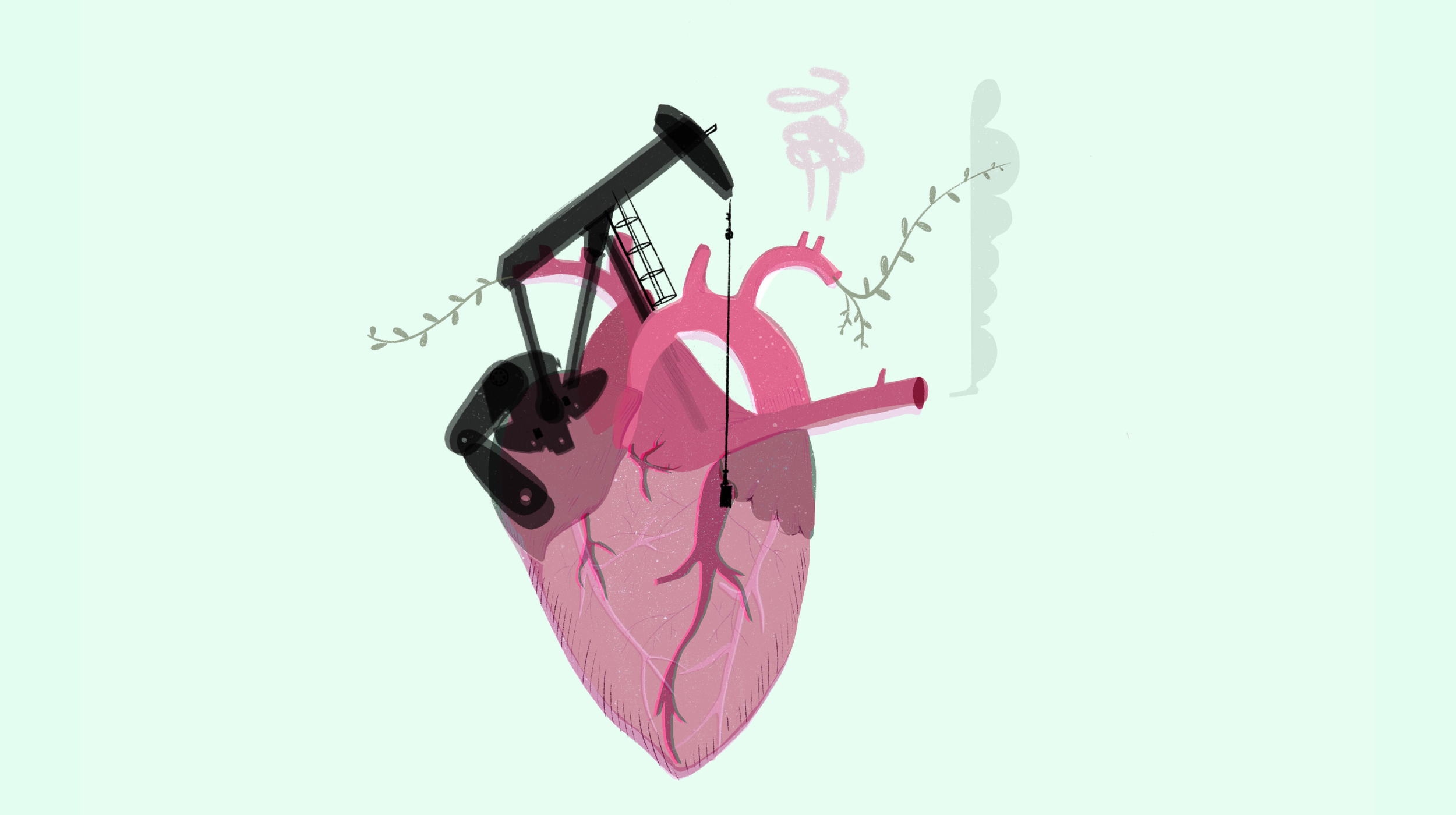

One of the most critical outcomes of COP30 will be the launch of the JTWP, which aims to provide guidance and support to countries transitioning to low-carbon economies without leaving anyone behind and while upholding the principles of equity and common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities (CBDR-RC). While all countries share a responsibility to tackle climate change, their historical contributions have varied from the least to the most. The equity and CBDR-RC principles enable a tailor-made approach that considers the contributions of each country. Rather than focusing just on replacing coal with wind or oil with solar, the programme considers how this transition may be done, who benefits from it, who bears the cost and who is included in the process. The JTWP is a crucial opportunity for States to implement climate action in a fair, inclusive and equitable way.

While SB62 began with three days of stalled negotiations, disagreements eventually gave way to progress on JTWP negotiations: slow, cautious but potentially significant. State positions during these JTWP negotiations varied wildly. Some States questioned whether the 1.5°C goal even aligned with the Paris Agreement, while others pushed to embed human rights at the heart of the transition. The result? A text with a wide variety of options to delay, dilute or delete text in three key areas:

Transitioning away from fossil fuels;

Finance for a just transition;

Establishing an implementation mechanism.

Key considerations for a just transition

Children and a just transition

As societies transition towards a low-carbon economy, children bear the brunt of the harmful effects of this transition, despite having contributed the least to the climate crisis. Their well-being depends heavily on the care of adults and the availability of strong social protection for their mental and physical health and development. Ensuring a clean, healthy and sustainable environment is not only an environmental imperative, it is also a legal duty, requiring both States and their parent(s)/carer(s) to provide children with an adequate standard of living.

However, current transition measures have already been shown to have a negative impact on vulnerable communities and children. Examples of harmful current measures include renewable energy projects and the extraction of transition minerals, which have in some cases involved child labour, violations of the right to education and the right to a healthy environment, as well as the destruction of key ecosystems that Indigenous children depend on.

To prevent the recurrence of such harms, CRIN advocates for a child-sensitive and child-rights-based approach to the JTWP. Transitions must include clear and enforceable safeguards grounded in accountability and international human rights law – including the Convention on the Rights of the Child and its General Comment 26, which elaborates on the right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment for children.

Advisory Opinions

Importantly, the recently published Advisory Opinion from the Inter-American Court of Human Rights on climate change has clarified the obligations of States under international law in relation to climate change. The Court clearly recognises that under the right to a healthy environment, the obligation of States to avoid irreversible climate and environmental harm is a jus cogens norm – a legal norm of the highest regard to which all states are bound. The Court also recognises the right to a healthy climate, where States have specific obligations to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions, especially in light of inter- and intra-generational equity. These obligations include setting appropriate mitigation targets, developing human rights-based climate strategies and, most importantly, regulating companies – obligations most governments have failed to fulfil so far.

The Court specifies six obligations under regulating companies, including adopting legislation to obligate companies to conduct human rights and climate change due diligence throughout their entire value chain. With such clear answers from the Court, States must be more ambitious and keep their legal obligations under international law in mind when determining their NDCs and when developing (among other key deliverables) the JTWP.

While we keep an eye out for the upcoming Advisory Opinion from the International Court of Justice on climate change, it is becoming increasingly clear that States' climate responsibilities are not just based on voluntary commitments, but also from binding legal obligations under regional and international law to protect current and future generations from the effects of climate change. States must increase their ambition to protect current and future generations from the effects of climate change.

Lessons from the past

To ensure accountability and long-term equity within the JTWP and its implementation mechanism, it is essential that both processes are informed by the experiences and lessons of sectors, such as (but not limited to) energy, (animal) agriculture, industrial and forestry. Each of these sectors provides strong evidence of how insufficient safeguards and weak regulatory oversight have led, and continue to lead, to serious and widespread human rights violations and environmental harm, particularly among already marginalised communities.

But these harms aren’t just isolated cases. They reveal systemic failures that risk being repeated.

That’s why the sectors driving the green transition, including critical transition minerals such as lithium, cobalt, and nickel, as well as renewable energy sources like solar and wind, must take these lessons seriously.

Protecting human rights and the environment can’t be an afterthought. It must be at the heart of the transition, ensuring that new industries don’t replicate the injustices of the past but instead pave the way for a truly just and sustainable transition.

Our key recommendations on the Just Transition Work Programme

Limit the fossil fuel sector’s influence during negotiations and institutionalise the meaningful inclusion of human rights and children’s rights to safeguard the integrity of the just transition. While fossil fuel interests remain deeply entrenched in the climate talks, their disproportionate presence (evidenced by the presence of over 1,700 fossil fuel lobbyists at COP29) has repeatedly undermined ambition and weakened climate decisions. The meaningful inclusion of human rights, children’s rights and the rights of other marginalised groups must be embedded through formal decisions and actionable commitments within the JTWP and its implementation mechanisms.

Rather than being limited to symbolic gestures, centring human rights, children's rights and the participation of marginalised communities in these processes is essential to counterbalance corporate interests and ensure decisions prioritise intergenerational equity.Call for a fair, fast, full and funded fossil fuels phase-out. Unless we directly confront and name the industries most responsible for the climate crisis, any talk of a "just transition" rings hollow. Especially since the continued burning of fossil fuels not only contributes to transboundary air pollution, it also exacerbates pre-existing health conditions and contributes to 8 million premature deaths annually. There can be no real transition without transforming the most polluting sectors.

Recognise the need to scale up new, additional, grant-based and highly concessional finance (meaning finance that benefits States over the market), particularly for developing countries undergoing a just and equitable transition. While the form of a just transition will vary depending on national contexts and capacities, it is essential to acknowledge and address the risk of deepening existing inequalities by ensuring equitable financial support.

Recognise and uphold social protection and the right to an adequate standard of living for all. This would apply both during and after the transition and include climate education and training for both children and their caregivers during the transition across sectors. This decision would guarantee the right to social security and a standard of living adequate for the child’s development. As the most widely ratified human rights treaty in the world, the Convention on the Rights of the Child should serve as a guiding instrument for ensuring intergenerational equity within the JTWP.

Treat the care economy as a core component of the JTWP. This includes recognising, valuing, and investing in paid and unpaid care work, much of which is disproportionately carried out by women and marginalised communities and also has a significant impact on children’s mental and physical development. A failure to integrate the care economy in the JTWP perpetuates structural inequalities and undermines the social foundations necessary for resilience in the face of transition economies.

Establish a JTWP implementation mechanism. Too many decisions lack enforcement and leave little to no impact. To be meaningful, the implementation mechanism must include the following preventive and restorative key elements:

Robust human rights-based impact assessment frameworks embedded within the system that are participatory, transparent and carried out prior to the approval of any transition-related project. These assessments must treat human rights as a fundamental pillar, not a procedural formality, throughout all stages of planning, implementation and evaluation.

Comprehensive risk and liability assessment frameworks that identify potential harm before project initiation. These assessments should explicitly integrate human rights risks, including the potential for displacement, livelihood loss and environmental harm, and must inform decision-making on whether and how a project should proceed.

Transparent community based monitoring and reporting systems, with the active participation of children, workers, youth, women and civil society to track progress, assess outcomes, and ensure course correction where needed. Accountability must be continuous, not retrospective.

Accessible and effective remedy mechanisms, both judicial and non-judicial, to address grievances, provide restitution and ensure accountability for any rights violations that arise in the course of the transition. These mechanisms should be designed in consultation with affected communities, children, Indigenous Peoples, youth, local communities, people with disabilities and civil society, and should be equipped to handle complaints in a timely and transparent manner.

Nationally Determined Contributions

After missing the initial February deadline, States are now expected to submit their third round of NDCs in September. NDCs are national action plans that outline a national pathway to a low-carbon economy and which must be submitted every five years under the Paris Agreement. While it’s encouraging that 60 countries mentioned human rights in the previous round of NDCs, it is far from being sufficient. NDCs must be grounded in intergenerational justice, equity and meaningful participation, including that of children while resisting corporate influence and aligning with the 1.5°C goal.

As a crucial part of the ‘implementation’ of a just transition, States must leave no one behind by adopting a fair, inclusive and equitable approach to developing their NDCs. Marshall Islands and Norway recently published their NDCs, which show promising ambition. Norway aims to reduce its emissions by 70-75% by 2035 compared to 1990 levels, while the Marshall Islands aims to reduce its emissions by 58% by 2035 compared to 2010 levels. Notably, civil society, especially the participation of children and youth and/or children’s rights, has played a crucial role in the process for both NDCs.

However, countries must be wary of false solutions and the tokenistic inclusion of children. Human rights and children’s rights must be integral to the NDCs themselves. New Zealand, Lesotho, Singapore, Japan and Switzerland’s latest NDC, published earlier this year, reveals a concerning lack of prioritisation of human rights, with children either not at all or barely mentioned, underscoring the urgent need for a rights-based approach.

A call to reform UN climate talks

While the climate talks in June continued as usual, over 200 civil society and Indigenous Peoples organisations, including CRIN, called for reform of the UN climate talks. After more than 30 years of little progress, business as usual is no longer acceptable. The message is clear: to make real climate action possible, the system itself must change. Meaningful change means introducing majority-based decision-making when consensus fails, ending corporate capture, ensuring the integrity of host countries and COP Presidencies, promoting radical transparency and accountability, upholding human rights, and aligning all outcomes with international law.

In solidarity with Gaza

The UNFCCC sessions cannot exist in isolation. While these spaces are dedicated to advancing climate action, they are inextricably linked to broader struggles for human rights and the prevention of atrocities. The UNFCCC Secretariat's decision to censor phrases like “End the Siege” at climate actions, either written or spoken, is unacceptable and an infringement on people’s freedom of speech. State Parties cannot claim to champion climate justice while remaining silent in the face of a genocide unfolding in real time. Climate justice is meaningless if it is not rooted in the protection of human dignity and life.

Conclusion

COP30 is a significant opportunity to deliver tangible climate action that protects our planet and upholds the rights of people and communities on the frontline of the climate crisis. This includes a JTWP and its implementation mechanism that drives a sustainable, inclusive and truly just transition, as well as the adoption of a rights-based approach to NDCs. Real and tangible action also means acknowledging and addressing the nexus between environmental destruction, climate change and conflict — including the ongoing genocide in Gaza, which is a reminder that climate justice cannot be separated from justice more broadly.

As calls for reform grow louder and stronger from organisations worldwide, decision-makers must treat COP30 as a Hail Mary: meaningful action is desperately needed and no one can be left behind. Anything less would mean a grand failure for current and future generations.

Will the 30th year of climate talks finally be the breakthrough that States need to meet the level of ambition to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees?

Read more perspectives on the JTWP and Bonn:

Global Campaign to Demand Climate Justice, ‘Civil society calls on Brazil’s COP30 Presidency: Deliver a Just Transition in Food and Agriculture’, 3 June 2025.

Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, ‘Workers want a Just Transition at COP30 in Belém’, 3 July 2025.

Carbon Brief, ‘Bonn climate talks: Key outcomes from the June 2025 UN climate conference’, 27 June 27 2025.