Introduction

What is the problem?

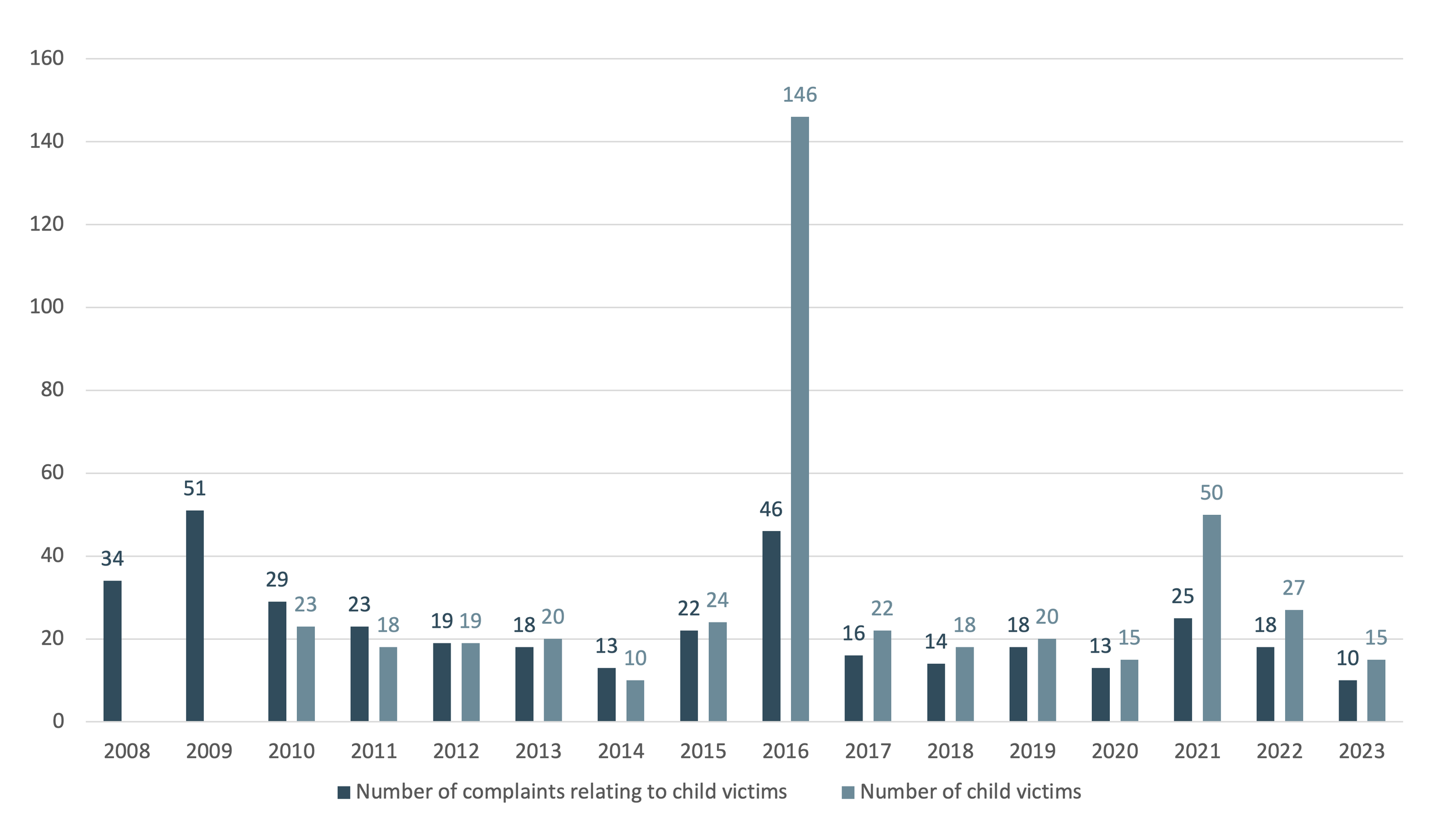

Sexual exploitation and abuse1 of children by United Nations (UN) peacekeepers is a long-standing, widespread, and continuing problem. These shocking violations are committed against some of the most vulnerable members of society and compound the suffering they already experience as victims of armed conflict. Complaints first emerged in the 1990s and have been made against military, police and civilian personnel of UN peacekeeping missions across many countries. Between 2004 and 2016 more than 300 allegations of sexual exploitation and abuse involving children were recorded globally (out of a total of 2,000).2 UN action over the last 20 years has proven to be largely ineffective in tackling the problem. A “Zero-Tolerance Policy” was adopted in 2003 prohibiting sexual exploitation and abuse by all UN personnel.3 The UN repeatedly renewed its commitment to the policy, and in March 2017 UN Secretary-General (UNSG) António Guterres launched a prevention and response strategy to address the problem.4 This led to some organisational changes and resulted in an increase in reporting,5 but it did not prevent further abuse, including of children. In 2017-2023, 114 further allegations involving children were recorded (out of a total of 459). Practitioners believe the actual numbers to be significantly higher.6 Ultimately, there continues to be near-total impunity for acts of sexual exploitation and abuse against children and adults alike, because of legal and political barriers to accountability within the UN system and in troop-contributing countries (TCCs), insufficient capacity to undertake criminal investigations, and a persistent lack of political will.Since 2015, statistics on allegations of peacekeeper sexual exploitation and abuse have been available through the Conduct in UN Field Missions table of allegations. The following graphs represent data concerning child victims extracted from the UN's public database.

Figure 1 provides information on allegations of sexual exploitation and abuse by year in which child victims are involved, as well as information on the number of identified child victims.

Figure 2 provides information on the number of allegations involving child victims, categorised by the nationality of the alleged perpetrators involved. If one allegation of sexual exploitation and abuse involves uniformed personnel from more than one troop-contributing country, the allegation is reflected for both countries.

| Nationality of alleged perpetrators | Number of perpetrators facing allegations involving children |

|---|---|

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | 23 |

| Gabon | 15 |

| Congo | 14 |

| Cameroon | 13 |

| Burundi | 11 |

| South Africa | 9 |

| Morocco | 9 |

| Tanzania | 9 |

| Nepal | 7 |

| Mauritania | 5 |

| Unknown | 5 |

| Pakistan | 3 |

| Bangladesh | 2 |

| Nigeria | 2 |

| Peru | 2 |

| Philippines | 2 |

| Senegal | 2 |

| Uruguay | 2 |

| Benin | 1 |

| Ghana | 1 |

| Guatemala | 1 |

| India | 1 |

| Niger | 1 |

| Paraguay | 1 |

| Romania | 1 |

| Rwanda | 1 |

What is CRIN doing about it?

CRIN started working on the issue of impunity in 2014, after the revelations of the sexual exploitation and abuse of children by international troops serving in the Central African Republic (CAR).9 Since then, the organisation has led several research and advocacy initiatives aiming to hold perpetrators (and the UN) accountable – with limited success.10

In 2019 we embarked on a project to analyse the reasons for this persistent impunity and how it could be addressed in order to tackle it more strategically. In addition to extensive desk-based research, we interviewed 30 UN officials, diplomats, NGOs, academics, journalists, activists and lawyers working on the issue of sexual exploitation and abuse in peacekeeping and humanitarian settings. We also worked with REDRESS11 to review attempts to hold perpetrators to account using litigation. REDRESS and CRIN then held a workshop with 13 key litigators, advocates and other experts from several countries, to explore avenues for legal advocacy.

This document is the result of all this work: it summarises the findings of our 2019 analysis and uses them to set out a strategy to promote accountability for child sexual exploitation and abuse by peacekeepers. Capitalising on the current UN momentum to prevent sexual exploitation and abuse, an effective response would push both the UN and TCCs to carry out reforms and improve access to justice for survivors. This strategy seeks to mobilise existing actors, initiatives and opportunities to create sustained pressure for meaningful change.

“When peacekeepers exploit the vulnerability of the people they have been sent to protect, it is a fundamental betrayal of trust. When the international community fails to care for the victims or to hold the perpetrators to account, that betrayal is compounded.”12

***

Footnotes

1 The UN defines sexual exploitation as “any actual or attempted abuse of a position of vulnerability, differential power, or trust, for sexual purposes, including, but not limited to, profiting monetarily, socially or politically from the sexual exploitation of another” and sexual abuse as “the actual or threatened physical intrusion of a sexual nature, whether by force or under unequal or coercive conditions” in Secretary-General’s Bulletin: Special measures for protection from sexual exploitation and abuse - ST/SGB/2003/13 (9 October 2003): https://undocs.org/ST/SGB/2003/13, p1. These definitions are endorsed by CRIN, including in Sexual Violence by Peacekeepers Against Children and Other Civilians – A Practical Guide for Advocacy (2016): https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5afadb22e17ba3eddf90c02f/t/6048a1a3eea85d105635dc5d/1615372756367/guide_-_peacekeeper_sexual_violence_final_0.pdf, p3. See also the Terminology Guidelines for the Protection of Children from Sexual Exploitation and Sexual Abuse (Luxembourg Guidelines): https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/TerminologyGuidelines_en.pdf

2 Paisley Dodds, AP Exclusive: UN Child Sex Ring Left Victims but No Arrests, AP News, Associated Press (12 April 2017): https://apnews.com/e6ebc331460345c5abd4f57d77f535c1

3 The policy prohibits UN staff from having any sexual relations with persons under the age of 18. UN Secretary-General’s Bulletin: Special measures for protection from sexual exploitation and sexual abuse - ST/SGB/2003/13 (9 October 2003): https://undocs.org/ST/SGB/2003/13

4 UN Secretary-General, Special measures for protection from sexual exploitation and abuse: a new approach - A/71/818 (28 February 2017): https://undocs.org/A/71/818

5 Reuters, “U.N. discloses rise in sex abuse cases, ascribes it to better reporting“ (19 March 2019): https://www.reuters.com/article/us-un-sexualviolence/un-discloses-rise-in-sex-abuse-cases-ascribes-it-to-better-reporting-idUSKCN1QZ2KV

6 Conduct in UN Field Missions, last accessed 13 July 2023: https://conduct.unmissions.org/sea-victims

7 Figures from the UN’s website on Conduct in Field Missions, Sexual Exploitation and Abuse, Table of Allegations (2015 onwards), last accessed 13 July 2023: https://conduct.unmissions.org/table-of-allegations

8 Figures from the UN’s website on Conduct in Field Missions, Sexual Exploitation and Abuse, Table of Allegations (2015 onwards), last accessed 13 July 2023: https://conduct.unmissions.org/table-of-allegations

9 “In the spring of 2014, allegations came to light that international troops serving in a peacekeeping mission in the Central African Republic had sexually abused a number of young children in exchange for food or money. The alleged perpetrators were largely from a French military force known as the Sangaris forces, which were operating as peacekeepers under authorization of the Security Council but not under United Nations command. The manner in which United Nations agencies responded to the allegations was seriously flawed.” See Marie Deschamps, Hassan B. Jallow and Yasmin Sooka, Taking action on SEA by peacekeepers: report of an independent review on SEA by international peacekeeping forces in the CAR (17 December 2015): https://reliefweb.int/report/central-african-republic/taking-action-sexual-exploitation-and-abuse-peacekeepers-report, p. i

10 Visit CRIN’s web page on “Sexual exploitation and abuse by UN peacekeepers” to find out more about actions we have taken since 2014 on this issue: https://home.crin.org/issues/sexual-violence/un-peacekeepers

11 REDRESS is an international human rights organisation that represents victims of torture to obtain justice and reparations. For more information, see www.redress.org

12 Marie Deschamps, Hassan B. Jallow and Yasmin Sooka, Taking action on SEA by peacekeepers: report of an independent review on SEA by international peacekeeping forces in the CAR (17 December 2015): https://reliefweb.int/report/central-african-republic/taking-action-sexual-exploitation-and-abuse-peacekeepers-report, p i