2. Why Are The Youngest Most At Risk?

Against the common assumption that military suicide is mainly caused by traumatic war experiences, the risk is highest among those who have never seen war.

Youth military suicide in particular is better explained by four other factors, which combine to magnify the risk:

- The adolescent brain’s heightened vulnerability to stress

- The troubled background common to young recruits

- The sustained stresses of early experiences in the military (particularly training)

- Difficulties readjusting to civilian life after leaving

2.1 War is not the reason

Most research on military suicide finds that being sent on deployment – a military operation – does not increase the risk,76 although certain types of war experiences, such as killing and injuring others, can do so.77

In any case, deployment cannot account for the higher risk in child recruits and veterans, who are not sent to war until they turn 18.78 Conversely, older personnel and veterans are likely to have been deployed several times yet have a suicide risk lower than the civilian average for their age.79

The heavy mental health burden carried by young soldiers and veterans even before they have seen war is better understood in terms of the stressful pathway taken by a typical child recruit.

2.2 The stressful career path of a child recruit

Every young recruit is an individual, but their experiences tend to bear certain characteristics in common, which combine to drive up the risk of mental ill-health:

- Stressful pre-military experiences. The army is twice as likely to recruit from the poorest local areas as from the richest80 and much of its intake already carries trauma from childhood.81

- Stressful military experiences. As described below, basic soldier training, particularly for the infantry, makes routine use of sustained stress and abuse is common.

- Stressful post-military experiences. A large proportion of child recruits drop out of their training, at which point they are immediately out of work and out of education.

When all these risk factors combine, as they frequently do, a picture emerges of a highly precarious recruit pathway. A teenager enlisted for the infantry from a troubled background, who suffers under the high-stress training environment and drops out without much support is likely to suffer mental health problems. The army does not track these discharged child recruits82 and they are unlikely to have contact with professional mental health services.83

2.3 Childhood stress and the adolescent brain

Predisposing factors

The developing adolescent brain is particularly vulnerable to stressors,84 especially social stressors such as bullying and ostracisation.85 Prolonged stress becomes toxic to the brain during this period, changing the way it functions and interfering with healthy development.86

Notably, sustained stress sensitises certain neural circuits.87 This can lead to anxious hyper-vigilance, for example, or aggressive outbursts, even when no stressors are present.88 It can also disrupt healthy brain development right into adulthood89 and induce lasting problems such as anxiety,90 depression,91 and substance misuse.92

While all of us are vulnerable to stress in our teenage years, susceptibility is aggravated in those whose earlier childhood was itself stressful.93 Adolescents with experience of abuse or neglect are more likely than others to be temperamentally anxious and depressive,94 for example, which dramatically adds to the risk of self-harm and suicide.95 By relying so heavily on child recruits from deprived neighbourhoods, the army’s recruitment strategy results in a high intake of young people already sensitised to stressors:

- Around half of young personnel have experienced at least four different types of adverse experience as children. 96, 97 This degree of traumatic exposure is indicative of lasting sensitisation to stress, as measured by the overproduction of cortisol.98

- These young, trauma-experienced personnel are much more likely than others to have problems with anxiety, depression, alcohol and substance misuse, self-harm, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).99 The rates of anxiety, depression, and PTSD among young personnel are approximately double those found in the same-age general population (Figure 11).100,101 All are risk factors for suicidality.

"Part of army training is to

break you down, but when you’re

16 your brain isn’t developed

properly... It has a massive effect

on your brain... It’s only later on

that you realise what’s been done

to you. It’s taken years and years

to now look back at that damage

that’s been done and build

myself back up."102

— Rachel, trained aged under 18.

Aggravating factors

Childhood stress has such a profound impact on later suicidality that it undoubtedly accounts in part for the elevated suicide rates found among young personnel and veterans, irrespective of their military experiences.103, 104

But the idea that early military experiences add nothing to this burden is untenable. That would be to argue that placing a stress-vulnerable adolescent child under the sustained stress of military training is harmless. All the available statistical evidence points the other way,105, 106 while veterans themselves offer their own compelling testimony that military training left them damaged.107

For example, if military enlistment had no harmful impact on trauma-experienced child recruits, they would not suffer greater stress-related mental illness than non-veterans from similar social backgrounds, but they do.

This is clearly shown later in Figure 7B for PTSD and, for suicidality, in Figure 6 below.

Taken together, the available evidence indicates that the mental health burden in adolescent recruits and veterans arises not from the impact of early life stress alone, but also from its aggravation by the stressors of their early military experiences.

As to why early military experiences are so stressful is the question to which we now turn.

2.4 The sustained stress of military training

The pressure cooker

The soldier has a job like no other. On the battlefield, they must run towards danger and kill and injure people, even when their every instinct is to flee. Accordingly, the main aim of basic military training is to inculcate unconditional obedience in recruits. It bears little resemblance to civilian notions of learning.109

To meet the unique demands of their role, new recruits must be coercively re-socialised. According to US military officers:

‘Intense indoctrination will be necessary to enable service members to engage in behaviours that represent a more radical departure from their prior experiences and worldview... (1) killing someone else in the service of a mission to protect one’s country, and (2) the willingness to subordinate self-interests, including survival, in the service of group goals.’110

The training environment is a pressure cooker; the military organisation subjects new recruits to continuous stress from their first day. The British army, for example, makes use of the following strategies to condition recruits for obedience:

- Capture. Child recruits to the army have no legal right to leave in the first six weeks.111

- Suppression. Uniforms and a ban on first names suppress the individual personality.

- Isolation. Strict limitations on contact with friends and family remove external sources of social support; in the first six weeks, child recruits are forbidden to host visitors or to leave the base to go into town, and they may only make one short phone call each evening (mobiles are confiscated on arrival).112

- Disorientation. Recruits are kept in the dark about what will happen, when, and why. They have no idea what is expected of them other than to do exactly what they are told.

- Depletion. Sleep deprivation and physical exhaustion deplete recruits’ capacity to resist the conditioning process; and

- Inducement. Obedience is conditioned by rewarding conformity and punishing failure with humiliation.113

An example of a conditioning technique is the humiliation of a recruit in front of their peers for not folding their clothes in precisely the way they have been told. While folding clothes is irrelevant to warfare, the repeating demand that every task be performed in exactly the way prescribed gradually induces recruits to follow any and every order without a second thought.114

"Bayonet training is teaching you to kill a person

with a blade on the end of a rifle. You’ll be put

through loads of physical punishments – you’re

crawling through mud, screamed at and shouted

at, kicked, punched while you’re on the floor,

anything to get you angry – they want you to

release this insane amount of aggression, enough

to stab another man when they say, basically, on

the flick of a switch... Every single person I spoke

to since leaving the army has been affected."

— Wayne, infantry, trained aged 17, 2006115

Mental health effects

Such coercive resocialisation would be unlawful in any civilian setting for any age group, yet this is how armies worldwide train their soldiers.117 The relatively little available research indicates a clear impact on mental health. A study of the US army, for instance, found that soldiers in training were four times as likely to attempt suicide as those on a first deployment (Figure 9).118, 119

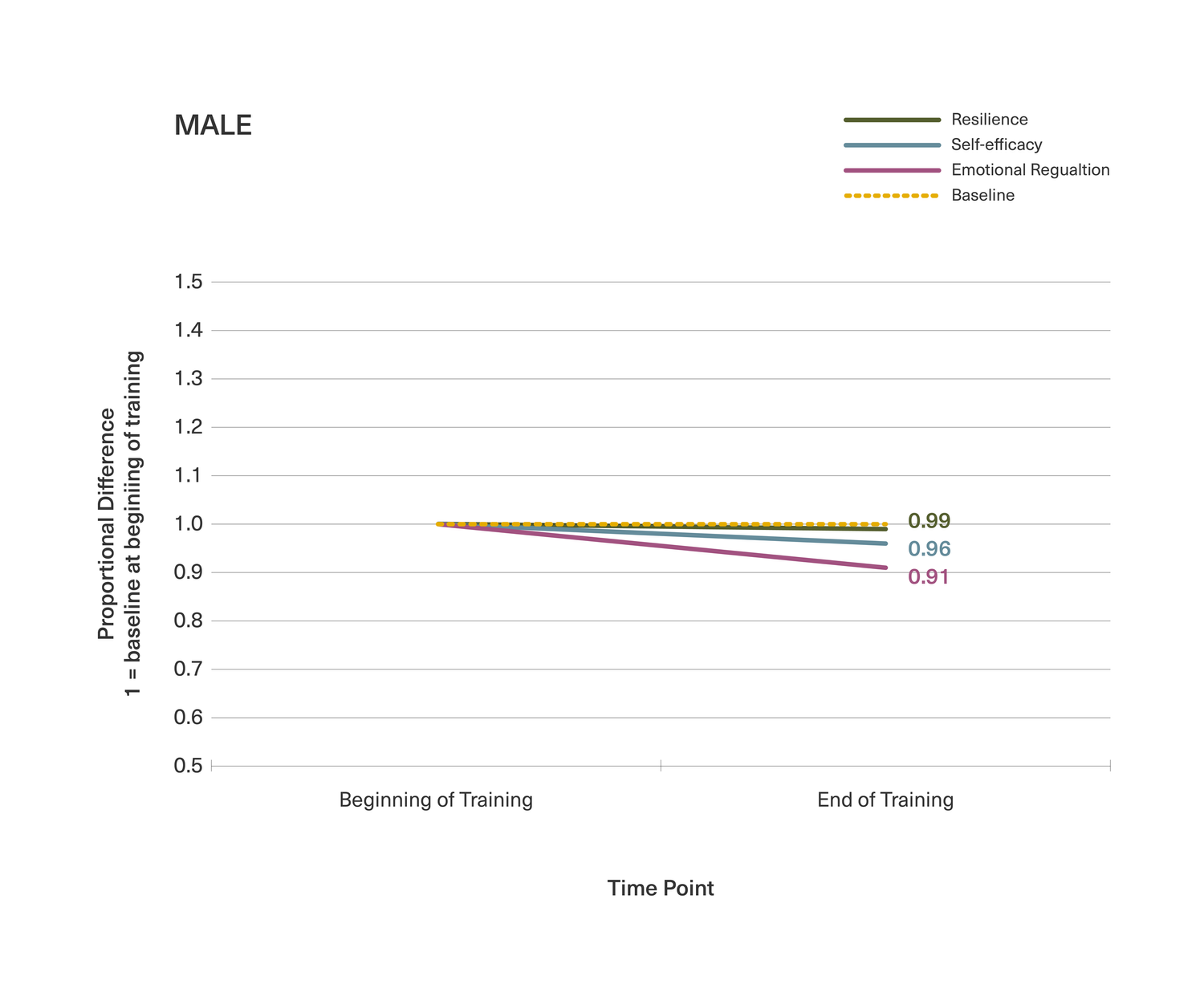

No comparable study has been carried out in the UK, but the British army’s own research in 2022 found that its child recruits specifically experienced an ‘erosion of resilience’ during initial training, as well as reduced self-belief and increased difficulties managing emotions (Figure 8):120

'In the female group there was a significant decrease in resilience, self-efficacy, emotional clarity, the ability to control impulses when distressed, and access to emotional regulation strategies after the training period. In the male control group there was a significant decrease in their reported ability to bounce back, [gain] access to emotional regulation strategies, and their overall emotional regulation scores after the training period.'121

These findings are consistent with the known effects of sustained stress on the adolescent brain.

"Unbeknown to me at the time, [the army’s]

training and/or indoctrination would come to

shape my life, my decisions and my neurological

processes for years to come... I suppose at the

time we took it all in our stride and laughed

it off. But we as people and in particular our

brains were being prepared for the inhuman

rigours and demands of traditional war fighting,

closing with and engaging the enemy and by

extension modern international conflicts."

— Ryan, British infantry, 2000-2008122

Army Training For Child Recruits:

A Culture Of Abuse

Listed below is some of the verifiable evidence of

serial abuse at the training centre for British army

recruits aged 16–171⁄2, the Army Foundation

College (AFC).

Between 2014 and February 2023, AFC recorded

72 formal complaints of violence against recruits

by staff, including assault and battery.123

Speaking to CRIN, parents of three recruits

at AFC have described routine maltreatment

by staff in some detail.124 Their children had

been punched, slapped, kicked, routinely called

the c-word and the f-word, and encouraged

to fight one another, for example. Recruits’

attempts to exercise their right to leave had

been intentionally obstructed. The parents also

testified to the traumatic effects of the abuse on

their children, which included suicidal ideation

and attempted suicide.125

Joe joined AFC at 16 in autumn 2013. He has

since described how staff:

- routinely assaulted recruits including him;

- related a detailed sexual fantasy of the rape of his girlfriend in order to induce extreme aggression in him;

- ordered him to strip to his underwear while a corporal ridiculed his body at length;

- laughed at him on several occasions when he was in evident distress; and

- repeatedly told recruits who asked for help to ‘piss off’ and ‘shut the f*** up’.126

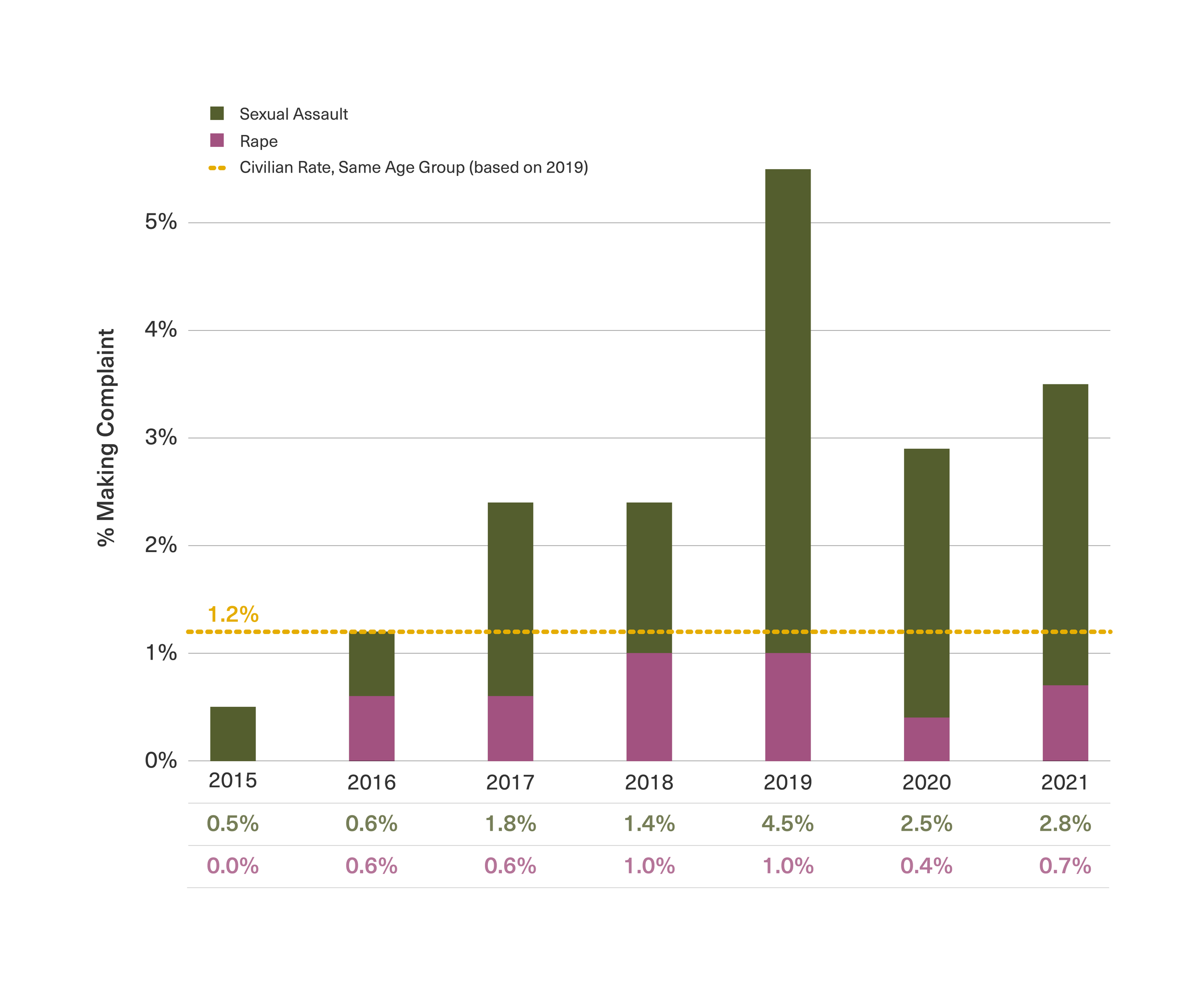

Across the armed forces, girls aged 16 or 17 are twice as likely as civilian girls of the same age to report a sexual assault or rape to the police.130,131 In 2021, one in every eight girls under 18 were victims of sexual offences, according to MoD records of police investigations; girls were ten times as likely as adult female personnel to be victimised in this way.132

Half of all girls who join the armed forces are enrolled for training at AFC.133 In 2021, 22 recruits at AFC were victims of sexual offences; three suspects were members of staff.134 The following year, an instructor was charged with five counts of sexual assault of 16-year-old female recruits.135

AFC’s own survey of female recruits in 2020 found that half had experienced bullying, harassment, or discrimination while training; fewer than a third said they would report such behaviour.136

Despite an evidenced culture of abuse persisting for at least a decade at the army’s dedicated training centre for child recruits, AFC has held an Outstanding Ofsted grade for welfare throughout.137,138 Ofsted has not reported the evidence of abuse, the very high trainee drop- out rate, or the legally enforced restrictions on recruits’ right to leave.139

Weeding out

From the day the child recruit arrives to train, stress is piled onto them. Recruits are disoriented, ordered around, and punished for mistakes. Some begin to bully others, so do some of the staff. For six weeks, denied the right to leave and mostly cut off from friends and family, and with little private space, the child recruit has no way to remove themselves from harm’s way.

The cumulative psychological load splits trainees into a majority ‘in-group’, who fall into line, and an ‘out-group’, a large minority who either resist the new demands or cannot keep up with them.140 While some in the in-group may thrive – and may be selected to provide testimonials for recruitment videos – the out-group suffers out of sight.

These pariah recruits bear the brunt of bullying by peers and staff. Young veterans and their parents have described daily experiences of social rejection, leading to low self-worth, emotional numbing, depression, despair, and/or suicidality.141 The ostracised child recruit is likely to leave when they can or get thrown out as unwanted – a third of the army’s child recruits never reach the end of their training.142

As the stresses of military training ‘weed out’ the unwanted, those young recruits prone to suicide become young veterans prone to suicide, and largely overlooked. Military suicide statistics in the UK are still calculated on the deaths of serving personnel alone.143

2.5 The young veteran’s predicament

The youngest veterans emerge from the armed forces with the stigma of rejection to face a precarious future. Not long ago they were in full-time education – most of their peers will still be there – and now they are ‘NEET’: not in employment, education, or training. Options for returning to education are now few, prospects for gainful employment uncertain.

A 2012 study found that nearly a half of veterans (all ages) who left the forces soon after joining had anxiety and/or depression.144 A fifth had PTSD,145 five times the rate found in the non-veteran population146 An earlier study found that twice as many veterans who left the forces soon after joining had suicidal thoughts when compared to those who had longer careers.147

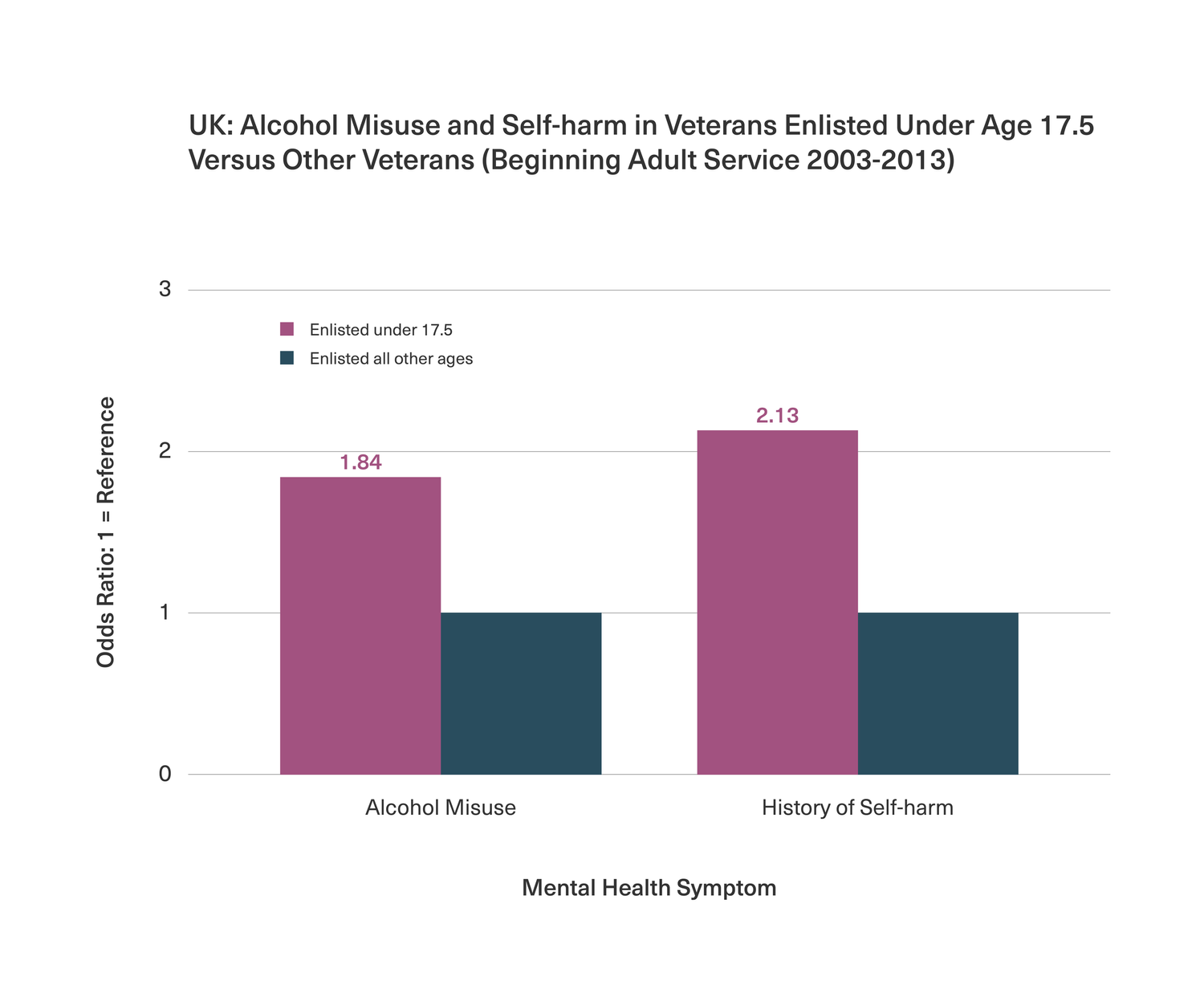

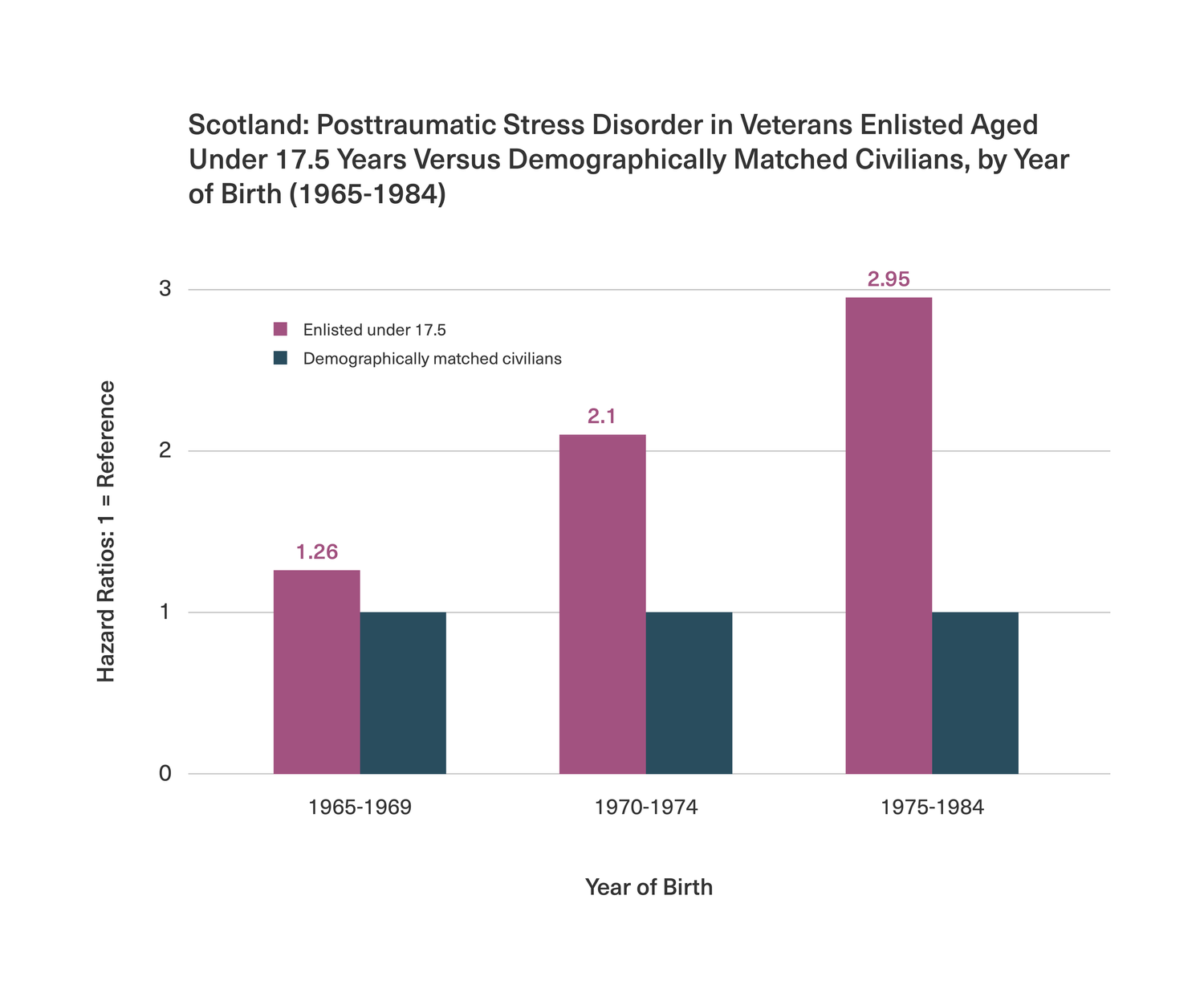

As noted earlier in Figure 4, veterans who joined up as children over the last two decades have been three times as likely as non-veterans of the same age to end their lives.148 Over a similar period, they have also had between two and three times the odds of long-term PTSD compared to same-age civilians from matched social backgrounds,149 and double the risk of alcohol misuse and of episodes of self-harm when compared with recruits who joined up older.150 This clearly disproportionate psychiatric burden is shown in Figure 7; the purple columns represent veterans who joined at the youngest ages.

Charlotte's

Story

Charlotte’s son Marc joined the Army Foundation College in 2016, aged 16.

[...] Just before he turned 16, Marc had a

recruiting day at school for the army. He

came home that evening elated and full of

enthusiasm to sign up. My husband and I

tried to convince Marc to get a trade or to

join the army later in a skilled role, but he

wanted to join up as soon as possible. He

was full of thoughts of seeing the world, of

travel, independence and high wages. [...]

We took him to an open day at the Army

Foundation College in Harrogate. All the

staff were charming and made Marc feel

like all his dreams could come true...

Regrettably, I signed Marc up on that day...

After Marc turned 17, he came home for

a week or two, and it was during this time

that I realised all was not well at Harrogate.

I overheard several conversations with

his fellow recruits discussing ‘bathroom

beatings’ and ‘things going too far’. Marc

also let slip he had been in several pubs,

bars and clubs in Leeds, and was actively

encouraged to attend strip clubs by the staff

members in charge of his group.

Marc struggles to talk about what happened

at Harrogate... but we know that staff bullied

and abused the young recruits, as well as

encouraging fighting amongst peers... He

and his fellow soldiers often reported feeling

very low, but this was ignored by the staff.

Marc is a completely different person since

his time at Harrogate. He has attempted

suicide and his mental health is permanently

damaged. He also sustained injuries while in

army training which may turn out to be life-

changing. Marc had to go AWOL [Absent Without Leave] from the army, and was only

discharged on mental health grounds after a

long fight, just over one year ago.

I strongly believe that the Army Foundation

College does not look after children’s

mental health or well-being. It is an outdated

institution where bullies thrive, and adults

seek pleasure in seeing children broken... I

am amazed the place is still allowed to ruin

children’s lives. They govern themselves and

the children are far too scared to speak up.

The adverts and the so-called ‘reality TV’

program which was aired on Harrogate

are completely fake and promise a life

which few young people can resist [but]

institutionalised bullying and abuse of

children is very much happening today... I

hope and long for this to change.

Read Charlotte’s testimony in full.

***

Footnotes

76 Department of National Defence (Canada), ‘2021 Report on Suicide Mortality in the Canadian Armed Forces (1995 to 2020)’, op cit.; Mia S Vedtofte, Andreas F Elrond, Annette Erlangsen, et al., ‘Combat exposure and risk of suicide attempt among Danish army military personnel’, 2021, The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 82(6), doi:10.4088/JCP.20m13251; Richard J Pinder, Amy C Iversen, Nav Kapur, et al., ‘Self-harm and attempted suicide among UK Armed Forces personnel: Results of a cross-sectional survey’, 2012, International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 58(4), 433–439, doi:10.1177/0020764011408534; Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center (US), ‘Deaths by suicide while on active duty, active and reserve components, U.S. Armed Forces, 1998-2011’, 2012, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22779434; Mark A Reger, Raymond P Tucker, Sarah P Carter, and Brooke A Ammerman, ‘Military Deployments and Suicide: A Critical Examination’, 2018, Perspectives on Psychological Science, 13(6), 688–699, doi:10.1177/1745691618785366; J Holmes, N T Fear, K Harrison, et al, ‘Suicide among Falkland war veterans’, 2013, BMJ, 346, doi:10.1136/bmj.f3204.

77 Mark A Reger et al., ‘Military Deployments and Suicide: A Critical Examination’, 2018, op cit.

78 Normally, no one under the age of 18 is deployed on operations.

79 See Figure 4.

80 The army recruits 0.7 individuals per 1,000 population aged 16–24 in the most deprived quarter of local authority areas, and 1.5 per 1,000 in the most privileged. Oxford Economics, 2021, op cit., p. 36.

81 Amy C Iversen, Nicola T Fear, Emily Simonoff, et al., ‘Influence of childhood adversity on health among male UK military personnel’, British Journal of Psychiatry, 2007, 191, 506–511, doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.107.039818.

82 James Heappey MP, ‘Army: Recruitment: Written question – 19893’, 24 February 2020, https://www.parliament.uk/business/publications/written-questions-answers-statements/written-question/Commons/2020-02-24/19893.

83 Rodway et al., 2022, op cit.

84 Marsh R, Gerber AJ, Peterson BS (2008): Neuroimaging studies of normal brain development and their relevance for understanding childhood neuropsychiatric disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 47 (11): 1233–1251, doi:10.1097/CHI.0b013e318185e703.

85 E B Quinlan, E D Barker, Q Luo, et al., ‘Peer victimization and its impact on adolescent brain development and psychopathology’, Mol Psychiatry, 2020, 25(1), pp.3066–3076, doi:10.1038/s41380-018-0297-9.

86 Campbell, 2022a, op cit.

87 Ibid.

88 Ibid.; C Heim, M Shugart, W E Craighead, and C B Nemeroff, ‘Neurobiological and psychiatric consequences of child abuse and neglect’, Developmental Psychobiology, 2010, 52(7), pp. 671–690.

89 Ibid.

90 Quinlan et al, 2020, op cit.

91 M F Van der Wal, C A de Wit, and R A Hirasing, ‘Psychosocial health among young victims and offenders of direct and indirect bullying’, Pediatrics, 2003, 111(6), pp. 1312–1317, doi:10.1542/peds.111.6.1312.

92 K Romer Thomsen, T Blom Osterland, M Hesse M, and S W Feldstein Ewing, ‘The intersection between response inhibition and substance use among adolescents’, Addict Behav, 2015, 78, pp. 228–230, doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.11.043.

93 Ibid.; M M Kishiyama, W T Boyce, A M Jimenez et al., ‘Socioeconomic disparities affect prefrontal function in children’, Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 2009, 21(6), pp. 1106–1115, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18752394; D Hackman and M J Farah, ‘Socioeconomic status and the developing brain’, Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 2009, 13(2), pp. 65–73, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19135405.

94 Table S4, Supplementary Appendix, linked from S J Lewis, et al., 2019, op cit.

95 Campbell, 2022a, op cit.; Heim, et al., 2010, op cit.

96 A Iversen et al., 2007, op cit.

97 By way of comparison, the same degree of exposure (four or more types of adverse childhood experience) is believed to have been experienced by around 8% of adults in the general population of England. M A Bellis, K Hughes, N Leckenby, et al., ‘Measuring mortality and the burden of adult disease associated with adverse childhood experiences in England: a national survey’, 2014, Journal of Public Health, 37(3), 445–454, doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdu065.

98 Kirsten Asmussen, Freyja Fischer, Elaine Drayton, and Tom McBride, Adverse childhood experiences: What we know, what we don’t know, and what should happen next (London: Early Intervention Foundation, 2020), p. 11.

99 Iversen et al., 2007, op cit.

100 Anxiety/depression in personnel under age 25 and same-age working civilians: 22% vs. 11%. L Goodwin, S Wessely, M Hotopf, et al., ‘Are common mental disorders more prevalent in the UK serving military compared to the general working population?’ Psychol Med, 2015, 45(9), pp. 1881-91. doi:10.1017/S0033291714002980.

101 PTSD in personnel under age 25 vs. same-age general population: 7% vs. 4%. S A M Stevelink, M Jones, L Hull, et al., ‘Mental health outcomes at the end of the British involvement in the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts: a cohort study’ (Supplementary Table 2), Br J Psychiatry, 2018, 213(6), pp. 690–697, doi:10.1192/bjp.2018.175; S McManus, P Bebbington, R Jenkins, and T Brugha (eds.), Mental health and wellbeing in England: Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2014, Leeds: NHS Digital, read here.

102 Cited in D Gee, 2017, op. cit., p. 56.

103 A recent study of Australian veterans, for example, found a strong association between the impact of childhood trauma, particularly anxiety disorders, and the ‘very high’ levels of suicidality it found in veterans. Rebecca Syed Sheriff, Miranda Van Hooff, Gin S Malhi, et al., ‘Childhood determinants of suicidality in men recently transitioned from regular military service’, 2020, Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 54(4), doi:10.1177/0004867420924742, 743–754.

104 US research indicates that stress in early life stress predicts around a third of adulthood psychiatric disorders. J G Green et al., ‘Childhood adversities and adult psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication 1: Associations with first onset of DSM-IV disorders’, 2010, Arch Gen Psychiatry, 67, 113–123.

105 For a survey of the evidence for the impact of adolescent stress on the childhood-traumatised mind, see Campbell, 2022a, op cit.

106 As shown in Figure 8, British army training has been found to erode psychological resilience and self-confidence and to make it harder to manage strong emotions.

107 See, for example, CRIN, 2021a, op cit.; Gee, 2017, op cit.

108 Sources for this figure are as follows: 1) General population: Office for National Statistics (ONS), 'Number and age-specific rate of suicides in young people, by IMD quintile in England, registered between 2001 and 2020', 2023, read here; 2) Armed forces personnel: Information obtained under the Freedom of Information Act, ref. 2023/01191, 17 February 2023, read here; 3) Army personnel: Ibid.; 4) Veterans: Rodway et al., 2022, op cit., Table 1.

109 P G Bourne, ‘Some observations on the psychosocial phenomena seen in basic training’, Psychiatry: Interpersonal and biological processes, 1967, 30(2), 187–196; D McGurk, D Cotting, T W Britt, and A Adler, ‘Joining the ranks: The role of indoctrination in transforming civilians to service members’, in A Adler, C A Castro, and T W Britt (eds.), Military life: The psychology of serving in peace and combat (Vol. 2: 'Operational Stress', pp. 13–31) (Westport, CT: Praeger Security International, 2006); D Gee, 2017, op cit.

110 McGurk, et al., 2006, op cit.

111 Under-18s cannot leave the armed forces at will; they have no right to leave at all during the first six weeks, after which a 14-day notice-period applies, and after the first six months a three-month notice period applies. The Army Terms of Service Regulations 2007, no. 3382 (as amended, 2008, no. 1849).

112 During the first six weeks, recruits are allowed ‘controlled access’ to their mobile phones for a 40–60 minute period between 8pm and 10pm; the rest of the time it is kept in a sergeant’s office. British army, 2018, op cit.

113 For a detailed description, see Gee, 2017, op cit.

114 According to US military officers: ‘The intense workload and sleep restriction experienced by military recruits leaves them little attention capacity for processing the messages they receive about new norms... Therefore, recruits should be less likely to devote their remaining cognitive effort to judging the quality of persuasive messages and will be more likely to be persuaded by the messages...’ McGurk et al., 2006, op cit., pp. 22–23.

115 For example, read Joe’s testimony in this report.

116 Calculated from MoD, Information obtained under the Freedom of Information Act, ref. 2021/09403, 21 September 2021, read here.

117 R J Ursano, et al., 2016, op cit.

118 US research has also found that suicides among never-deployed soldiers have been highest in the infantry, where they were three times as frequent as in the rest of the army. R C Kessler, M B Stein, PD Bliese, et al., ‘Occupational differences in US Army suicide rates’, Psychol Med, 2015, 45(15), pp. 3293-3304, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26190760.

119 Army Foundation College Harrogate, 2022, op cit., pp. 28, 38.

120 Ibid., p. 34.

121 Cited in Gee, 2017, op cit., p. 59.

122 Ibid. pp. 57-58.

123 Between 2014 and February 2023, AFC recorded 72 formal complaints of violence against recruits by staff, including assault and battery. At least 13 of these cases were proven following investigation. Leo Docherty MP, 2022a, op cit., and 19 May 2022 (2022b), read here. Information obtained under the Freedom of Information Act, ref. Army/Sec/C/U/FOI2021/13445, 30 November 2021, read here and ref. Army/Sec/C/U/FOI2021/15645, 11 January 2022, read here and ref. Army/Sec/U/A/FOI2023/02395, 23 March 2023, read here; Johnny Mercer MP, ‘Army: Young people – no. 109376’, 4 November 2020, read here.

124 Cited in CRIN, 2021a, op cit.

125 Ibid.

126 Ibid.

127 S Morris, ‘UK army investigators under fire as bullying trial collapses’, The Guardian, 19 March 2019, https://theguardian.com/uk-news/2018/mar/19/uk-army-investigators-under-fire-as-bullying-trial-collapses.

128 Ibid.

129 Mark Guinness, A Review of the Royal Military Police investigations into allegations of the ill treatment of Junior Soldiers at the Army Foundation College (Harrogate) (AFC(H)) 2014/15, 2018, read here.

130 Between 2015 and 2020 inclusive, the armed forces service police recorded 31 sexual offences against girls aged 16–17, representing an average rate of 2.5% in the age group. In 2020, for example, the service police recorded eight sexual offences against girls in the age group, who numbered 280 at the time (8 / 280 = 2.9%). Information obtained under the Freedom of Information Act, ref. FOI2021/09403, 21 September 2021; MoD, ‘UK armed forces biannual diversity statistics: 2021’, 2021, https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/uk-armed-forces-biannual-diversity-statistics-2021.

131 In 2019–20, police in England and Wales recorded 101,478 sexual offences (assault or rape) committed against women and girls, of which 7.3% (7,408) affected girls aged 16–17, representing a rate of 1.2% (7,408 offences / 618,095 population aged 16–17 in 2019). ONS, ‘Dataset: Sexual offences prevalence and victim characteristics, England and Wales (2019-20)’, 2020, https://tinyurl.com/ons-sexual-offences-2019-20; ONS, ‘Population estimates for the UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland: mid-2020’ (Figure 8, 2019, England and Wales only), 2020, https://tinyurl.com/ons-pop-2019.

132 In 2021, 37 girls were victims in sexual offence cases opened by the Service Police, out of a total population of 290 girls serving in the armed forces; a rate of 12.8%. In the same year, 202 adult female personnel were victims of sexual offence cases, out of a population of 16,180, a rate of 1.2%. Leo Docherty MP, 2022a, op cit.; MoD, Sexual Offences in the Service Justice System 2021 Annual Statistics [Worksheet 3], 31 March 2022d, read here; MoD, UK armed forces biannual diversity statistics: 1 April 2021 [Tables 1 and 3], 10 June 2021, read here.

133 In the five years from 2017–18 to 2021–22, 1,430 girls were enlisted in the armed forces, of whom 735 (51%) were enrolled for training at the Army Foundation College. Andrew Murrison MP, ‘Army Foundation College: Admissions’, 17 November 2022, https://questions-statements.parliament.uk/written-questions/detail/2022-11-17/89849; MoD, UK armed forces biannual diversity statistics: April 2022 (Data tables), 2022a, https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/uk-armed-forces-biannual-diversity-statistics-april-2022, Table 9.

134 Leo Docherty MP, 2022a and 2022b, op cit.

135 Marc Nicol and Richard Eden, ‘Sex abuse claims hit Army college for teenage recruits as instructor is charged with more than 20 offences including five allegations of sexual assault against 16-year-old girls’, Mail on Sunday, 23 October 2022, https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-11346043/Sex-abuse-claims-hit-Army-college-teenage-recruits.html.

136 Army Foundation College Harrogate, 2022, op cit., p. 5.

137 According to Ofsted reports over the last decade, welfare outcomes at AFC have been ‘good’ (2013), recruits ‘feel safe’ (2018), and the college has an ‘ethos of emotional and psychological safety’ (2021). See Ofsted, ‘Welfare and duty of care in armed forces initial training’, 2022, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/welfare-and-duty-of-care-in-armed-forces-initial-training.

138 The most recent Ofsted report is available at MoD, ‘Nine armed forces settings rated good or outstanding under Ofsted new inspection regime’, 2021, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/nine-armed-forces-settings-rated-good-or-outstanding-under-ofsted-new-inspection-regime.

139 For details, see letter from CRIN to Ofsted, 18 November 2021, with reply dated 7 December 2021, read here.

140 For examples, see Gee, 2017, op cit.; CRIN, 2021a, op cit.; and B Griffin, The making of a modern British soldier [video], 2015.

141 See, for example, CRIN, 2021a, op cit.; Gee, 2017, op cit.

142 In the three-year period 2015–16 to 2017–18, the army enlisted 5,280 recruits aged under 18, of whom 1,580 (30.0%) dropped out before completing their Phase 2 training. Applied to 2021–22, when the army enlisted 2,030 children, a 30% dropout rate is equivalent to c. 600 individuals per year. Calculated from MoD, 2022a, op cit. and Heappey, 2020, op cit.

143 MoD, ‘UK armed forces suicides: Index’, 2022e, https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/uk-armed-forces-suicide-and-open-verdict-deaths-index.

144 J E Buckman, H J Forbes, T Clayton, et al., ‘Early Service leavers: a study of the factors associated with premature separation from the UK Armed Forces and the mental health of those that leave early’, 2013, European Journal of Public Health, 23(3), 410–415, doi:10.1093/eurpub/cks042. The study examined the prevalence of mental health problems in veterans who left the forces within their four years. Since the right to leave expires after the first few months, most veterans in this ‘four year’ group will have left in their first few months.

145 Ibid.

146 The point prevalence of PTSD in the general population of the UK is approximately 4%. PTSDUK, ‘Post Traumatic Stress Disorder stats and figures’, 2022, https://www.ptsduk.org/ptsd-stats.

147 C Woodhead, R J Rona, A Iversen, et al., ‘Mental health and health service use among post-national service veterans: results from the 2007 Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey of England’, Psychol Med, 2011, 41(2), pp. 363–372. doi:10.1017/S0033291710000759.

148 Rodway et al., 2022, op cit., Table 1.

149 Bergman et al., 2021, op cit.

150 Jones et al., 2021, op cit.

151 Jones et al., 2021, op cit.; Bergman et al., 2021, op cit.