Youngest Most At Risk

While the risk of suicide among British armed forces personnel is lower than that found in civilian life, this is not so among the youngest soldiers, who are much more likely than their civilian peers to end their lives. The risk is highest of all in child recruits who leave soon after joining.

1.1 Youngest Recruits

Over the last 20 years, suicide in the British armed forces has been less common than among civilians of the same age. 45 This is not so for male soldiers aged 16–19, whose risk has been one-third (31%) higher than that of same-age civilians46 and three times the average for the armed forces as a whole.47

This high risk is mostly confined to the army; the risk to young air force and navy personnel has resembled that faced by civilians of the same age.48

Figure 1 shows how high the risk has been for young soldiers. The bold horizontal line in each graph shows the suicide rate in the general population for the same age group; the red line shows the rate in the army. The first graph shows the suicide rate since 2001 in the under-20 age group.

1.2 Women and Girls

Since female personnel are a small minority of the armed forces, calculating their suicide rate reliably is not possible.51 Suicide among female former personnel (i.e. 'veterans') follows a similar pattern to men: overall, the risk is little different from civilian life, but among the youngest it is between three and four times higher.52

The experience of other countries suggests that, in general, female personnel and veterans are at increased risk relative to their civilian peers, though less is known about the specific risks of younger age groups:

- In the United States, whose armed forces are large enough to calculate a rate of suicide among serving female personnel, their risk is approximately twice that of civilian women.53

- In Australia and Canada, female veterans have been around twice as likely as their civilian peers to end their lives,54 and in the United States three times as likely.55

Given the dearth of data on female or transgender military suicide in the UK, the rest of this report focuses on the risk among males.

1.3 Infantry

As mentioned, youth suicide risk in the armed forces is concentrated in the army. Within the army, it is concentrated in the infantry. These are close-combat troops who make up just over a quarter of army personnel.

The army says that the reason it recruits soldiers from age 16 is ‘particularly for the infantry’56 and child recruits are indeed over-represented among infanteers.57

| Military branch/arm | Average number of male personnelE | Confirmed suicidesF | Average suicides per year | Crude annual suicide rate per 100,000 personnel |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARMY | 91,186 | 185 | 9.3 | 10.1 |

| Infantry | 24,933 | 64 | 3.2 | 12.8 |

| Exc. Infantry | 66,253 | 121 | 6.1 | 9.1 |

| NAVY | 33,422 | 46 | 2.3 | 6.9 |

| Marines | 6,628 | 10 | 0.5 | 7.5 |

| Exc. Marines | 26,794 | 36 | 1.8 | 6.7 |

| AIR FORCE | 36,791 | 36 | 1.8 | 4.9 |

Table 1: Data for figure 2 – suicides among British armed forces personnel, by military branch (males, 2001–2020).

Reference E: Army/navy/air force personnel figures from Esme Kirk-Wade and Noel Dempsey, UK defence personnel statistics, 2022, read here; infantry personnel figures obtained under the Freedom of Information Act, ref. ArmyPolSec/D/N/FOI2022/10712, 7 October 2022, read here; marines personnel figures obtained under the Freedom of Information Act, ref. FOI2022/11421, 19 October 2022, read here.

Reference F: Male army/navy/air force suicide figures obtained from Additional table 2 in MoD, ‘UK armed forces suicides: 1984 to 2021 data tables’, 2022, read here; infantry suicide figures obtained under the Freedom of Information Act, ref. ArmyPolSec/D/N/FOI2022/10712, op cit.; marines suicides figures obtained under the Freedom of Information Act, ref. FOI2022/11421, op cit.

| Age at entry | IntakeA (missing data 2005/06 - 2006/07) | Estimated intake adjusted for missing dataB | SuicidesC | Odds ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16-17 | 25,075 | 28,561 | 36 | 2.3 (95% CI 1.4-3.7 p = 0.0013) |

| 18+ | 45,320 | 50,356 | 28 | 1 (reference) |

| Other Ranks | 42,686 | 47,429 | — | — |

| Officer CadetsD | 2,634 | 2,927 | — | — |

Table 2: British infantry, 2001–2020: odds of in-service suicide by age at enlistment.

- A: Andrew Murrison MP, ‘Army: Recruitment’, 23 November 2022, read here.

- B: To make this adjustment, we have assumed that intake in the two years for which data are missing is proportional to the 18 years for which data is available, and therefore multiplied the 18 years’ available data by 20/18 – i.e., by a factor of 1.111.

- C: Information obtained under the Freedom of Information Act, 14 November 2022, op cit.

- D: The minimum age for entry as an officer cadet is 18.

Infanteers have a very high suicide risk (Figure 2), which is concentrated in soldiers who signed up as children: over half of infanteers who died by suicide in the last two decades joined up under age 18 (Figure 3).59 Between 2001 and 2020, infanteers who had joined up under the age of 18 had more than double the odds of in-service suicide as soldiers who had joined up as adults [OR 2.3, 95% CI 1.4-3.7, p=0.001].60

1.4 Youngest Veterans

The risk of suicide and other mental health problems increases after personnel leave. In around the last two decades, the youngest veterans – which here means all ex-personnel, whether they have been to war or not – have been three times as likely as same-age civilians to end their lives.62

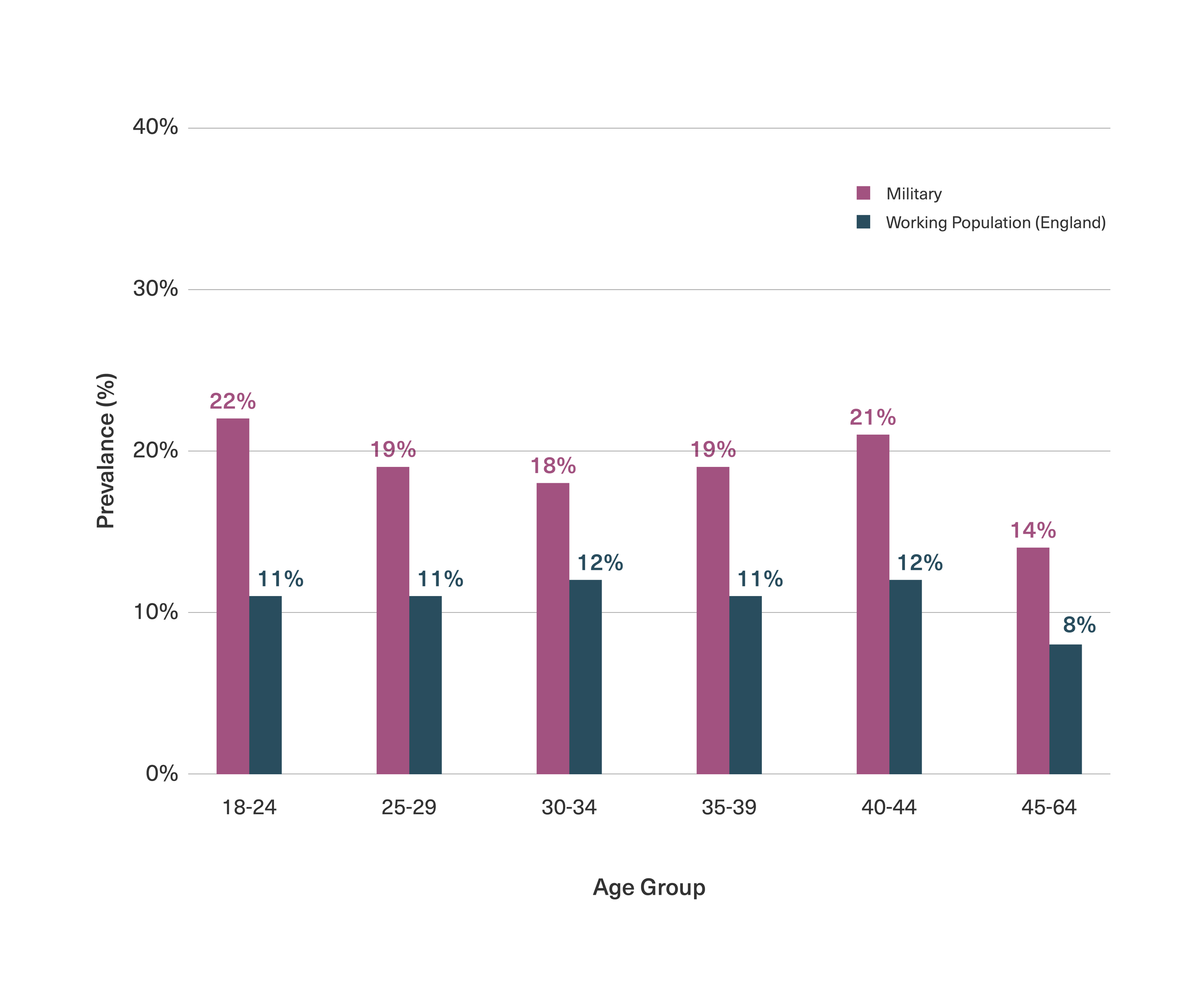

Figure 4 presents the findings of the study in question, showing how strongly the risk of veteran suicide is concentrated among the youngest. The dotted line shows the civilian suicide rate for each age group; the purple column shows the rate of suicide in the youngest veterans.

In an earlier study by the same team, veterans who had both joined up and left at 16 had had the highest suicide risk of all.63 Evidently, child recruits who leave service early – which usually means during their initial training – face a markedly elevated risk of suicidality.

1.5 International Comparison

A similar pattern is seen in other economically comparable countries that enlist child recruits (Figure 5).65 As in the UK, so in Australia, Canada, and the United States, the risk is concentrated in the army and especially army veterans.66, 67

In respect of serving personnel, research in the US found that many more attempted suicides in the US Army were by soldiers in training than by those at war.68 In respect of veterans, other research in the US found that veterans with less than one year’s service – who tend to be those who dropped out of their training – were much more likely than longer-serving veterans to end their lives.69 As in the UK, so in Canada and the US (though not in Australia), most cases of veteran suicide occur in the few years after discharge.70

Alison's Story

Alison’s son Nathan joined the Army Foundation College in 2016, aged 16.

Nathan started his military career at the

Army Foundation College Harrogate in

2016. Nathan was a confident, resilient

lad who wanted nothing more than to be

a soldier. [...] During the first phase of his

training Nathan reported serious incidents

to me; he told me he was hit, slapped,

pushed, kicked and verbally abused by staff.

He said he felt humiliated... He knew the

training would be tough but this was abuse

and the staff were power crazy. [...]

Nathan felt uncomfortable talking about

what was happening to him but I often

pushed him to open up and talk to me.

He did tell me about witnessing abuse of

his peers and commented on his dislike

and distrust for some of the staff. He did

however point out not all staff were abusive

but said that none of them could be trusted.

He told me all staff knew what was going

on but turned a blind eye. [...]

After the initial six weeks of training we

travelled to Harrogate for Nathan’s first

passing out parade and brought him

home on leave. He was not the same

happy confident lad who started six weeks

previously. He started drinking heavily and

was very withdrawn. It was very difficult

getting him to return to Harrogate and he

told me he wanted to leave the army.

When he returned to Harrogate, he rang

me to tell me he was handing in his letter

to leave. He told me his request was ripped

up in his face. He was only 17 years old

and devastated at not being able to leave.

He repeatedly told me he wanted to be a

soldier and expected training to be tough

but couldn't cope with the way they were

mistreated. He was clearly very frightened

for his safety and I shared his fears.

Whenever he was on leave it became

increasingly difficult to get him to return

to Harrogate. I would take him to the train

station and by the time I arrived home

Nathan wouldn't be far behind me. He was

genuinely very fearful of being at Harrogate

and things just got worse... He didn't mind

the legitimate punishments, it was the

abuse he was scared of.

I spoke to his commanding officers after

every occasion and expressed my concerns.

Each member of staff basically said the

same thing: if Nathan didn't return he would

be posted AWOL. I was repeatedly told

[incorrectly] that once he had completed

the first six weeks he had no way of leaving.

They said no matter how he felt he had to

complete the four years. [...] The officers

told me that if Nathan didn't return then the

seriousness of the situation would escalate

and the punishments would be more severe.

[...] He described the staff as animals that

got off on hurting and humiliating people

and that Harrogate should be shut down.

Nathan died while still serving in the army.

Read Alison’s testimony in full.

***

Footnotes

45 Between 2001 and 2020, the suicide rate in the UK armed forces overall was 57% lower than that found in the same-age general population. MoD, ‘UK armed forces suicides: 1984 to 2021 data tables’, 2022b, read here.

46 Between 2001 and 2020, the suicide rate in army personnel aged 16–19 was 31% higher than that found in the same-age general population. Ibid.

47 Between 2002 and 2021, the standardised mortality ratio for suicide among soldiers aged 16–19 in the UK was 131 (i.e. a 31% increased risk relative to the same-age general population) and 43 in the armed forces as a whole (i.e. a 57% reduced risk relative to the same-age general population), a threefold difference. UK MoD, 2022b, op cit., Additional Table 4.

48 The suicide rate in young personnel relative to same-age general population between 2002 and 2021 has been 51% lower than the same-age general population in the air force and 1% lower in the navy. The relatively higher rate found in the navy could be due in part to marine commandos, who make up its intensively trained, ground close-combat arm. Ibid.

49 Ibid., see additional Figure 10 in source cited.

50 Goodwin et al., 2015, op cit.

51 MoD, Suicides in the UK regular armed forces: Annual summary and trends over time, 2022c, read here.

52 Rodway et al., 2022, op cit.

53 Department of Defense, 2020, op cit.; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022, op cit.

54 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, ‘Serving and ex-serving Australian Defence Force members who have served since 1985: suicide monitoring 2001 to 2019’, 2021, read here; Kristen Simkus, Amy Hall, Alexandra Heber, and Linda VanTil, ‘2019 Veteran Suicide Mortality Study’, 2020, Veterans Affairs Canada, read here, Table 5.

55 The suicide rate among US female veterans in 2019 was 15.4 per 100,000, and among women in the general population in 2020 it was 5.5 per 100,000. Department of Defense 2020, op cit.; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022, op cit.

56 According to the MoD, Junior Entry recruitment (aged 16–17.5 years) ‘presents an opportunity to mitigate Standard Entry (SE) shortfalls, particularly for the Infantry’ (‘SE’ refers to ‘standard entrants’, meaning recruits aged 17.5 years and above at date of enlistment). MoD, Policy on recruiting Under-18s (U18), 2013, obtained under the Freedom of Information Act, Ref. FOI2015/00618, 12 February 2015, p. 2, https://tinyurl.com/wzos8xw.

57 In the five-year period between 2016–17 and 2020–21, 10,140 army enlistees were aged under 18, of whom 3,898 (38%) were in the infantry, and 29,160 enlistees were aged 18 and above, of whom 8,710 (30%) were in the infantry. Calculated from information obtained under the Freedom of Information Act, 22 September 2021, ref. FOI2021/10665, read here, and MoD, UK armed forces biannual diversity statistics: April 2021 (Data tables), 2021, read here, Table 9A.

58 Information obtained under the Freedom of Information Act, 14 November 2022, op cit.

59 See Table 2 for figures and sources.

60 See Table 1 and 2 for sources and detail.

61 Information obtained under the Freedom of Information Act, 14 November 2022, op cit.

62 Rodway et al., 2022, op cit., Table 1.

63 N Kapur, D While, N Blatchley, et al., ‘Suicide after leaving the UK armed forces — A cohort study’, PLOS Medicine, 2009, 6(3), 2009, doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000026.

64 Rodway et al., 2022, op cit., Table 1.

65 Note that the particularly high suicide rate shown for the UK armed forces is likely due to the younger average age in the youngest age group defined, rather than indicating that military life in the UK is more stressful than in other countries.

66 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2021, op cit., see Table 5; Department of National Defence (Canada), 2022, op cit., Figure 1; Department of Defense, 2020, op cit., Table 2; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022, op cit., Table 1.

67 In the US, for example, the suicide rate for active personnel aged 17–19 in 2020 was 36% higher than that found in a similar age group in the general population. Specifically, the suicide rate among US active-component (cf. ‘regulars’ in UK) personnel aged 17–19 was 30 per 100,000 and the rate in the male general population aged 15–24 was 22 per 100,000. Department of Defense, 2020, op cit., Table 2; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022, op cit., Table 1.

68 R J Ursano, R C Kessler, J A Naifeh, et al., ‘Risk factors, methods, and timing of suicide attempts among US army soldiers’. JAMA Psychiatry, 2016, 73(7), 741–749, doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.0600.

69 M A Reger, D J Smolenski, N A Skopp, et al. ‘Risk of suicide among US military service members following Operation Enduring Freedom or Operation Iraqi Freedom deployment and separation from the US military’, JAMA Psychiatry, 2015, 72(6), pp. 561–569, read here.

70 H K Kang, T A Bullman, D J Smolenski, et al., ‘Suicide risk among 1.3 million veterans who were on active duty during the Iraq and Afghanistan wars’, Ann Epidemiol, 2015, 25(2), pp. 96–100, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25533155; Kristen Simkus and Linda VanTil, ‘2018 Veteran Suicide Mortality Study: Identifying Risk Groups at Release’, 2018, read here; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2021, op cit., Table 9.

71 Australia: Relative risk for veterans aged under 30 = x1.68, derived by dividing veteran rate (34.0 per 100,000) by the rate in the same-age general population (20.2 per 100,000). Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2021, op cit., Table 3.

72 Canada: Relative risk for veterans aged under 25 = x2.52. Kristen Simkus et al., 2020, op cit., Table 3.

73 UK: Relative risk for veterans aged 16–19 = x3.05. Rodway et al., 2022, op cit., Table 1.

74 US: Relative risk for veterans aged 18–34 = x1.93, derived by dividing veteran rate (50.6 per 100,000) by the same-age non-veteran rate (26.2 per 100,000). US Department of Veterans Affairs, ‘2001-2019 National Suicide Data Appendix’, op cit.

75 Ursano et al., 2016, op cit.